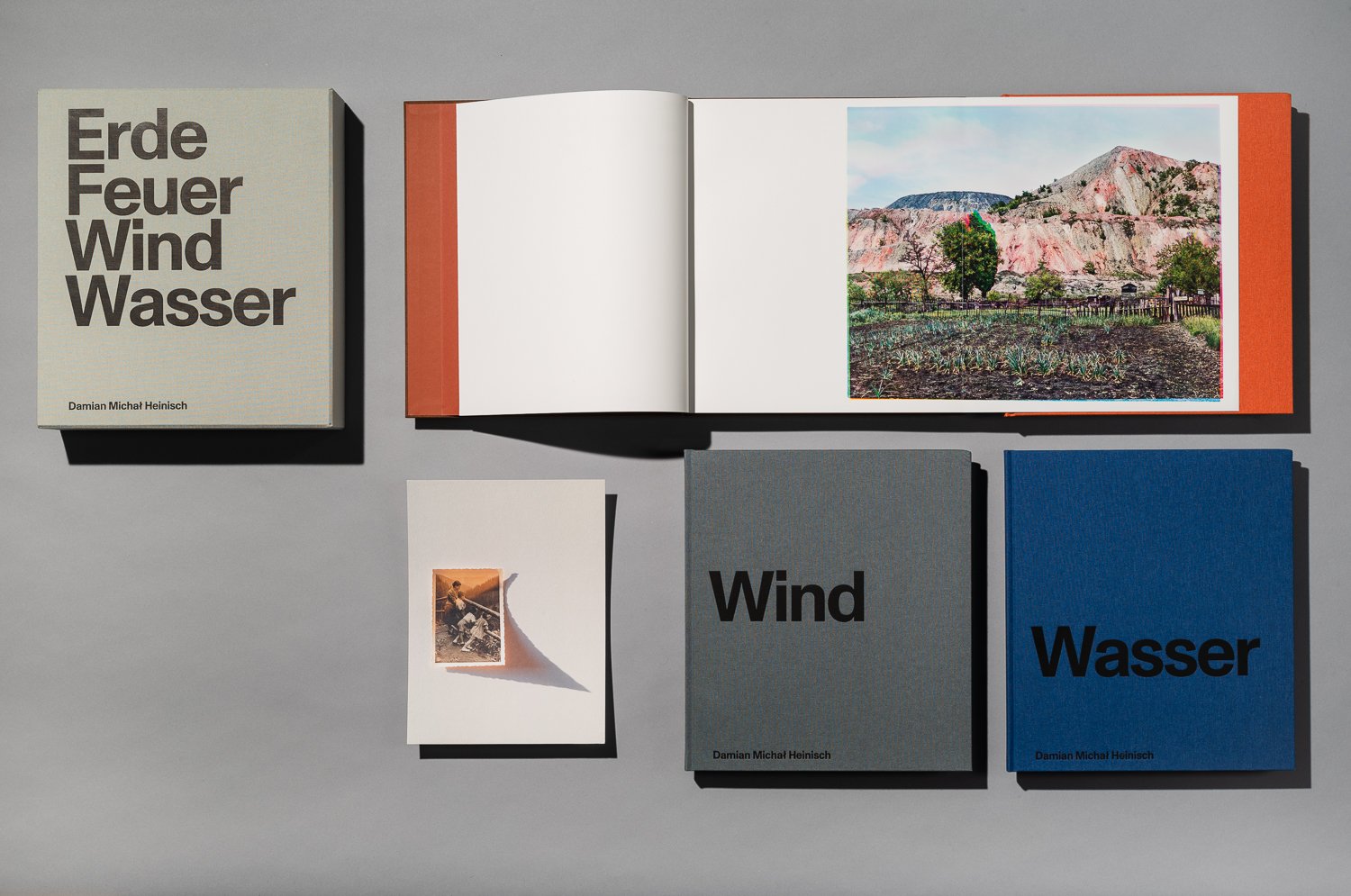

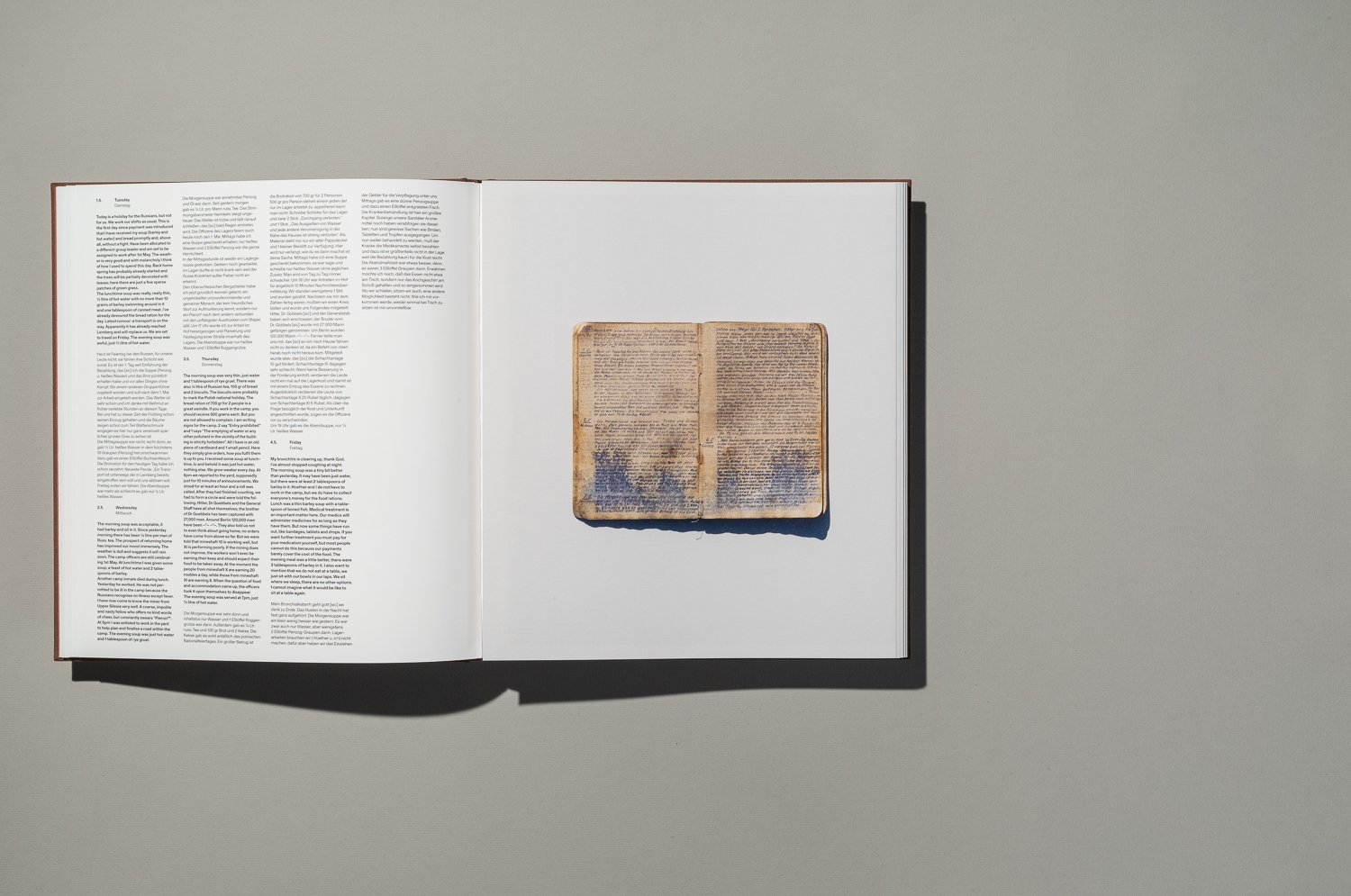

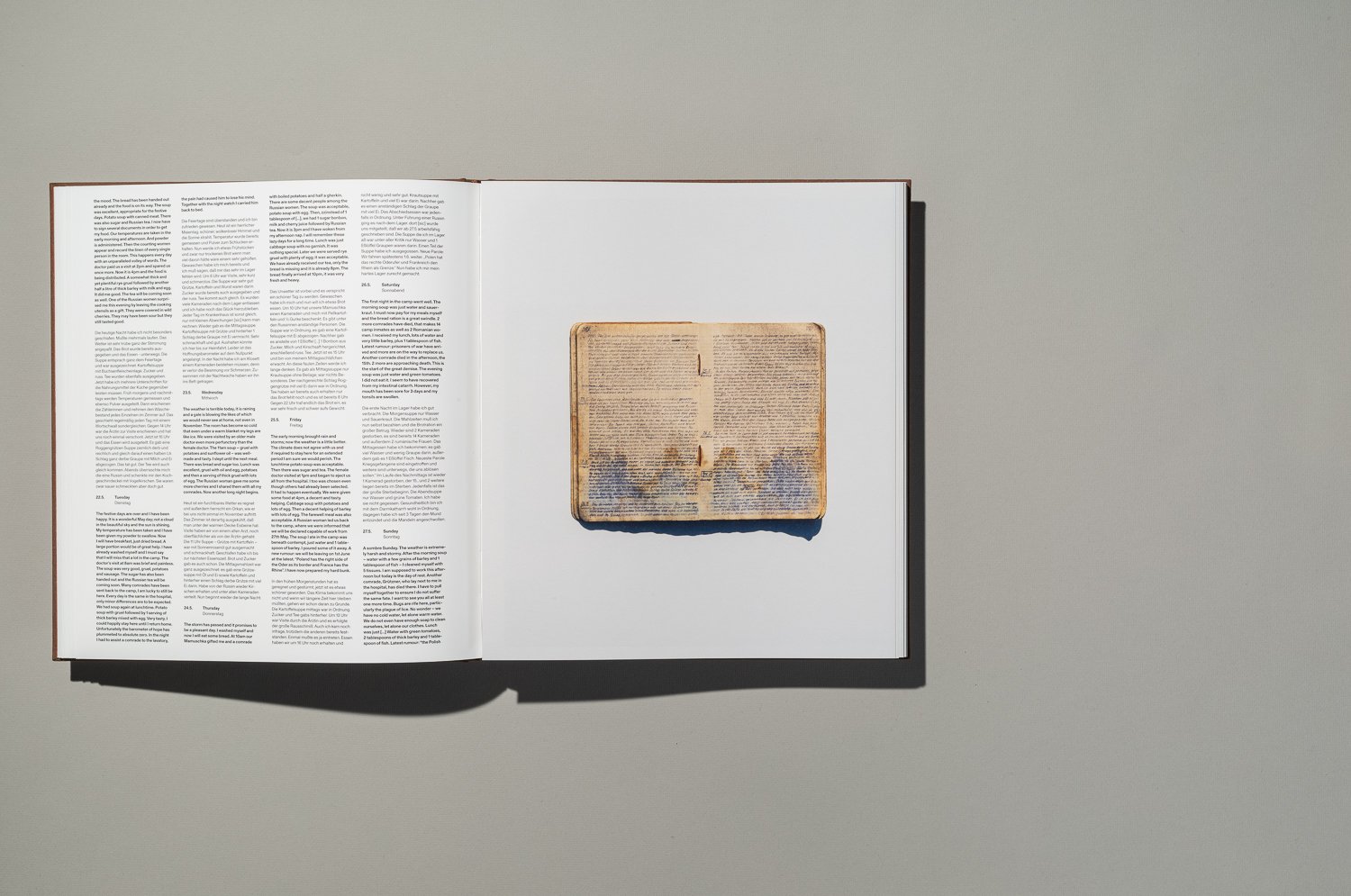

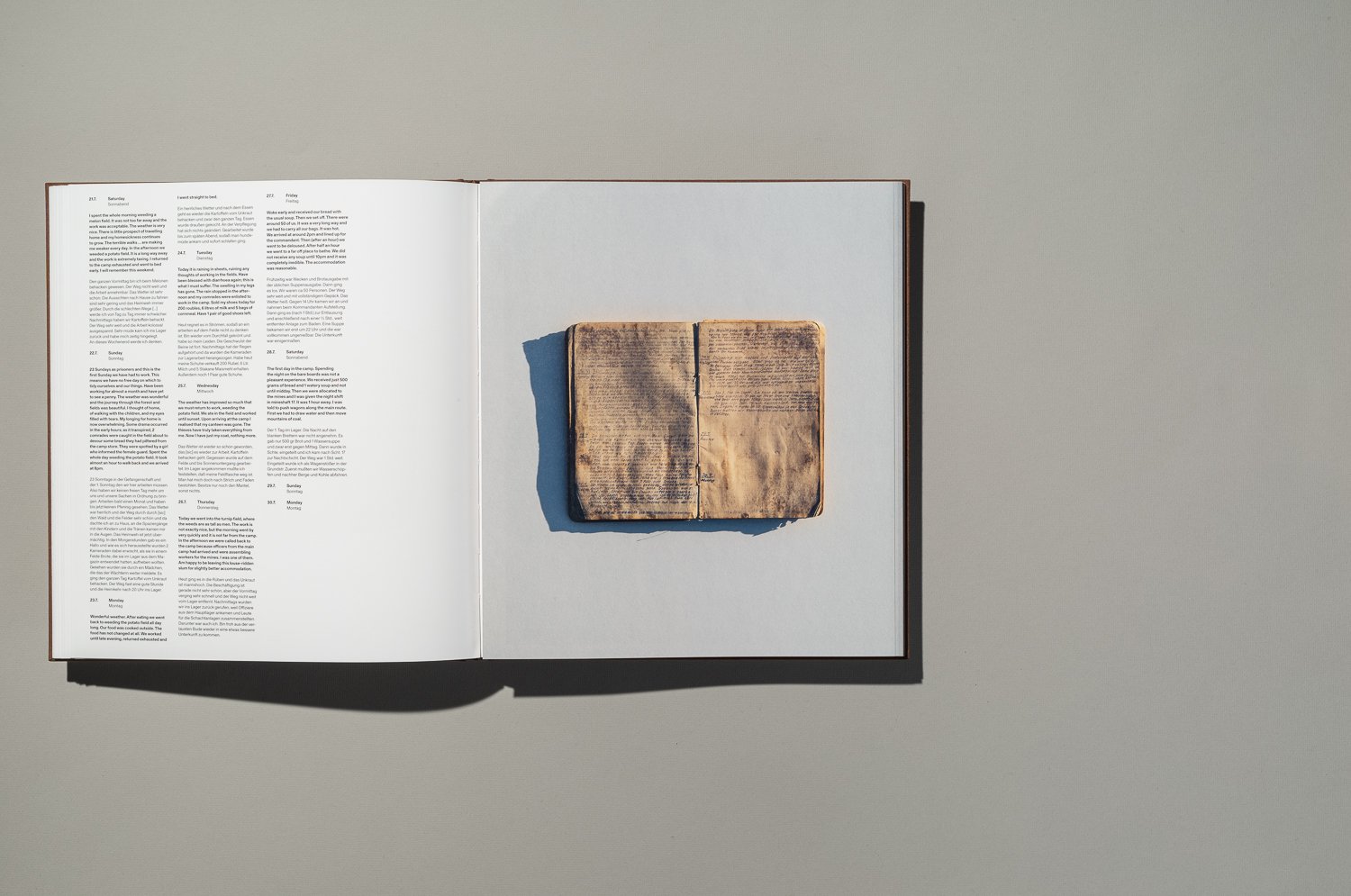

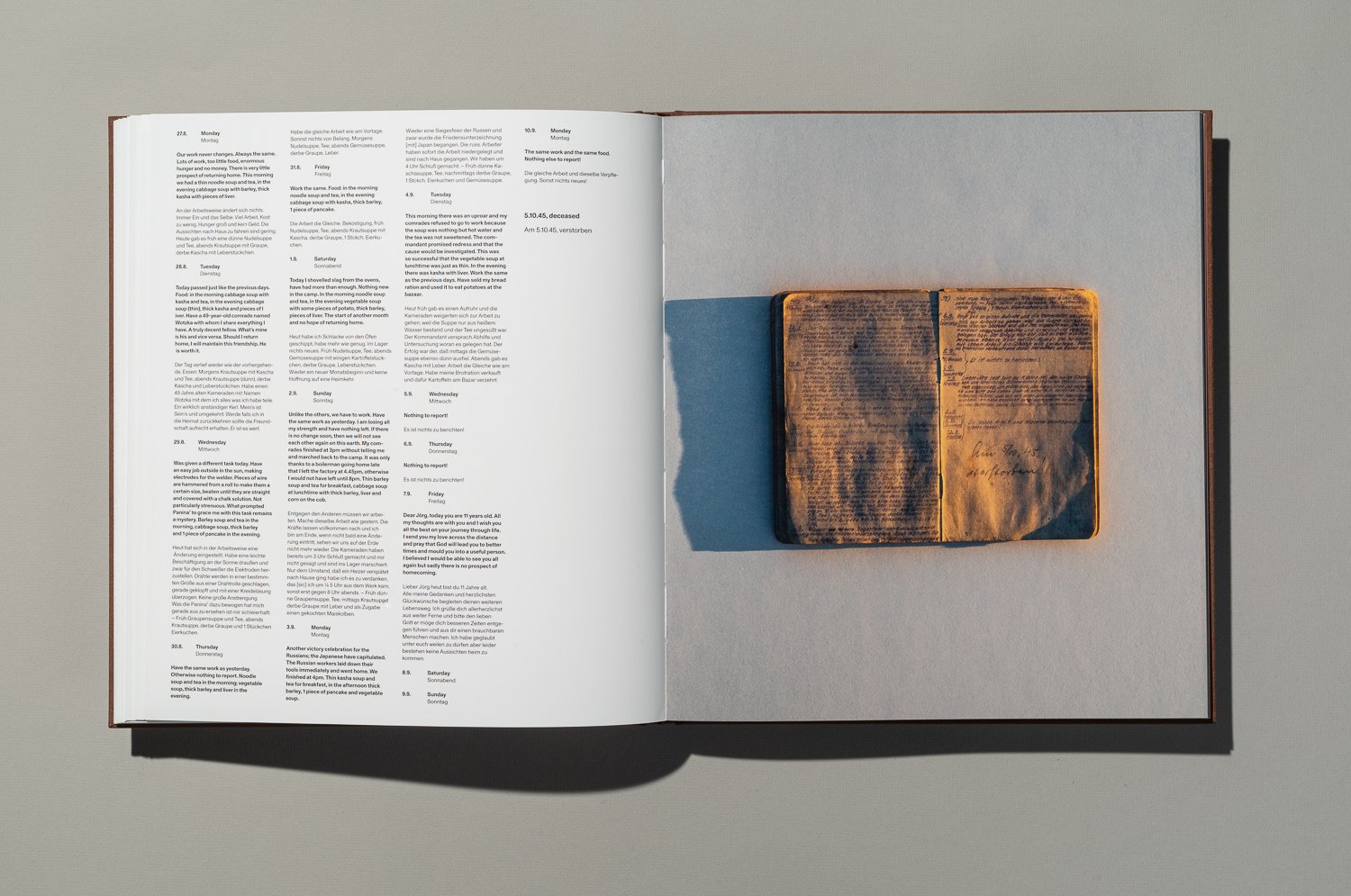

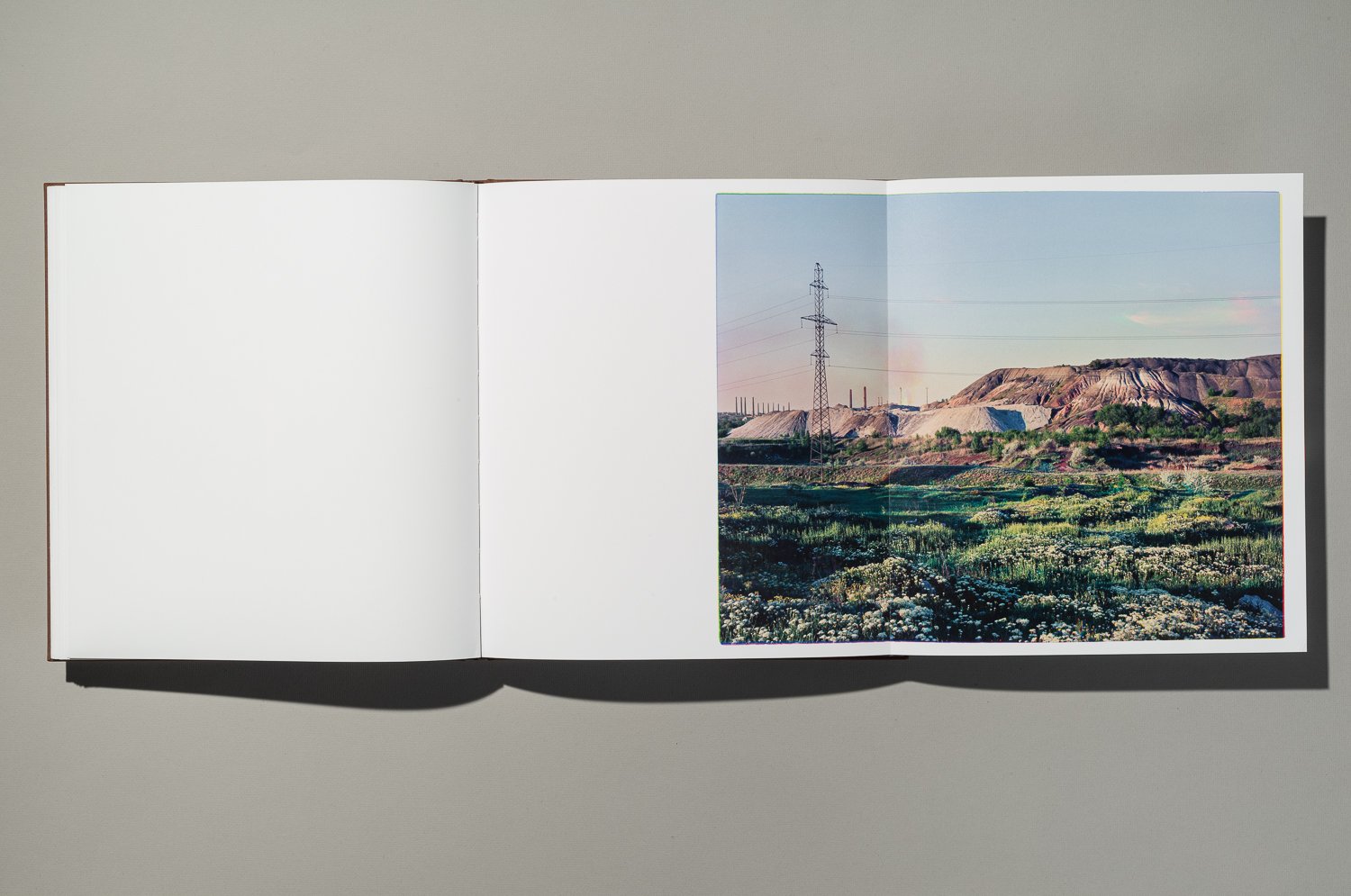

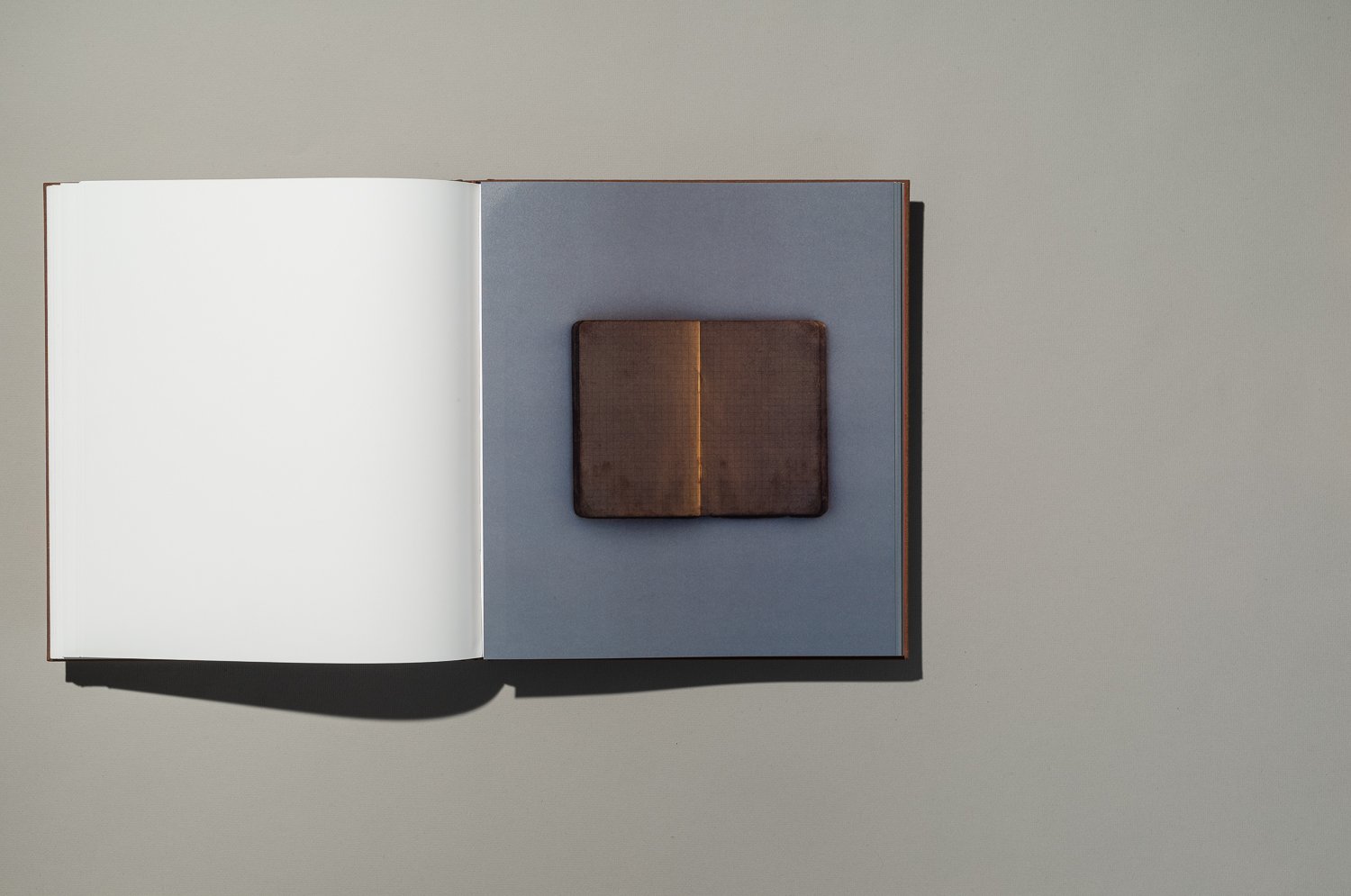

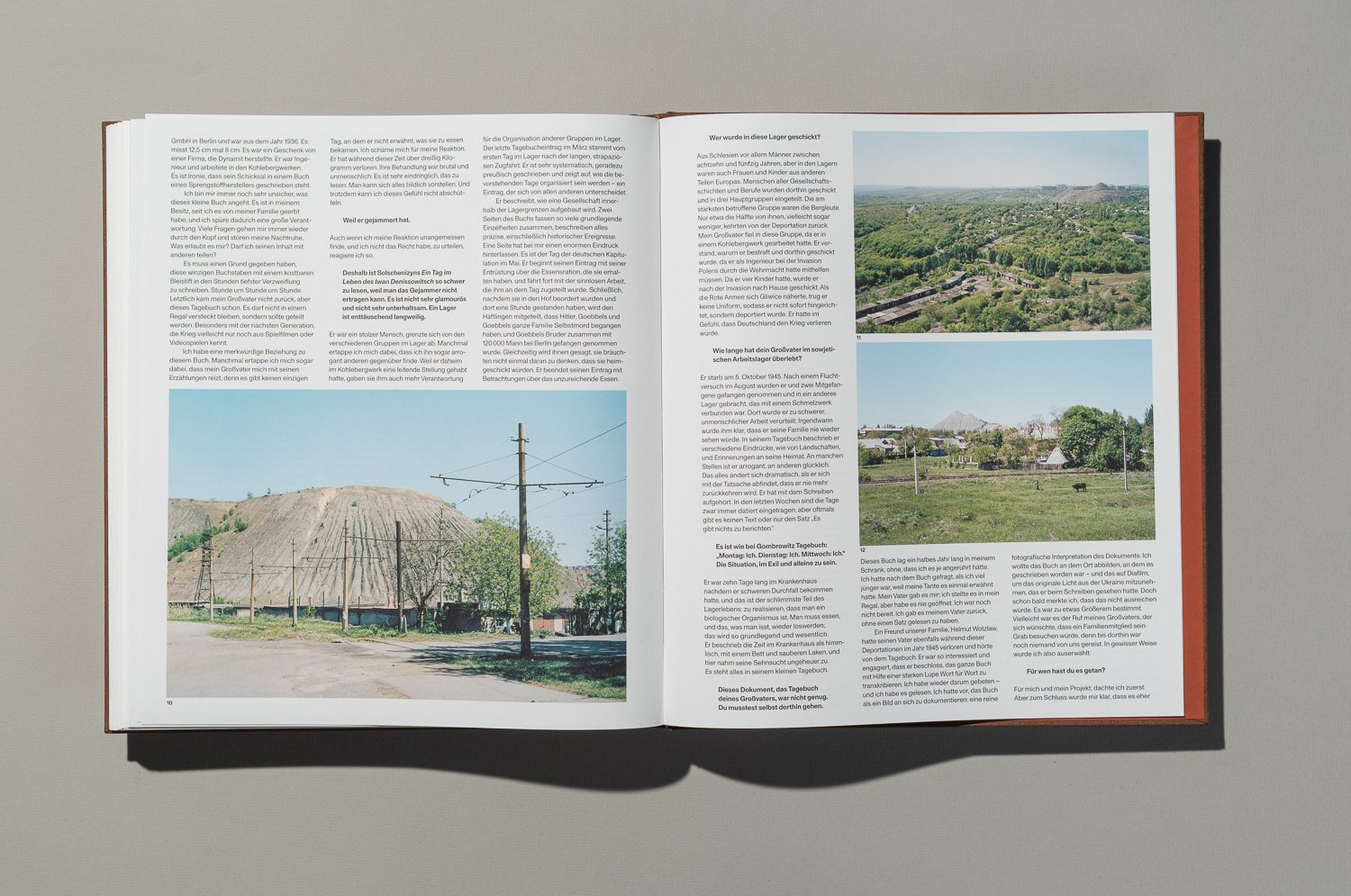

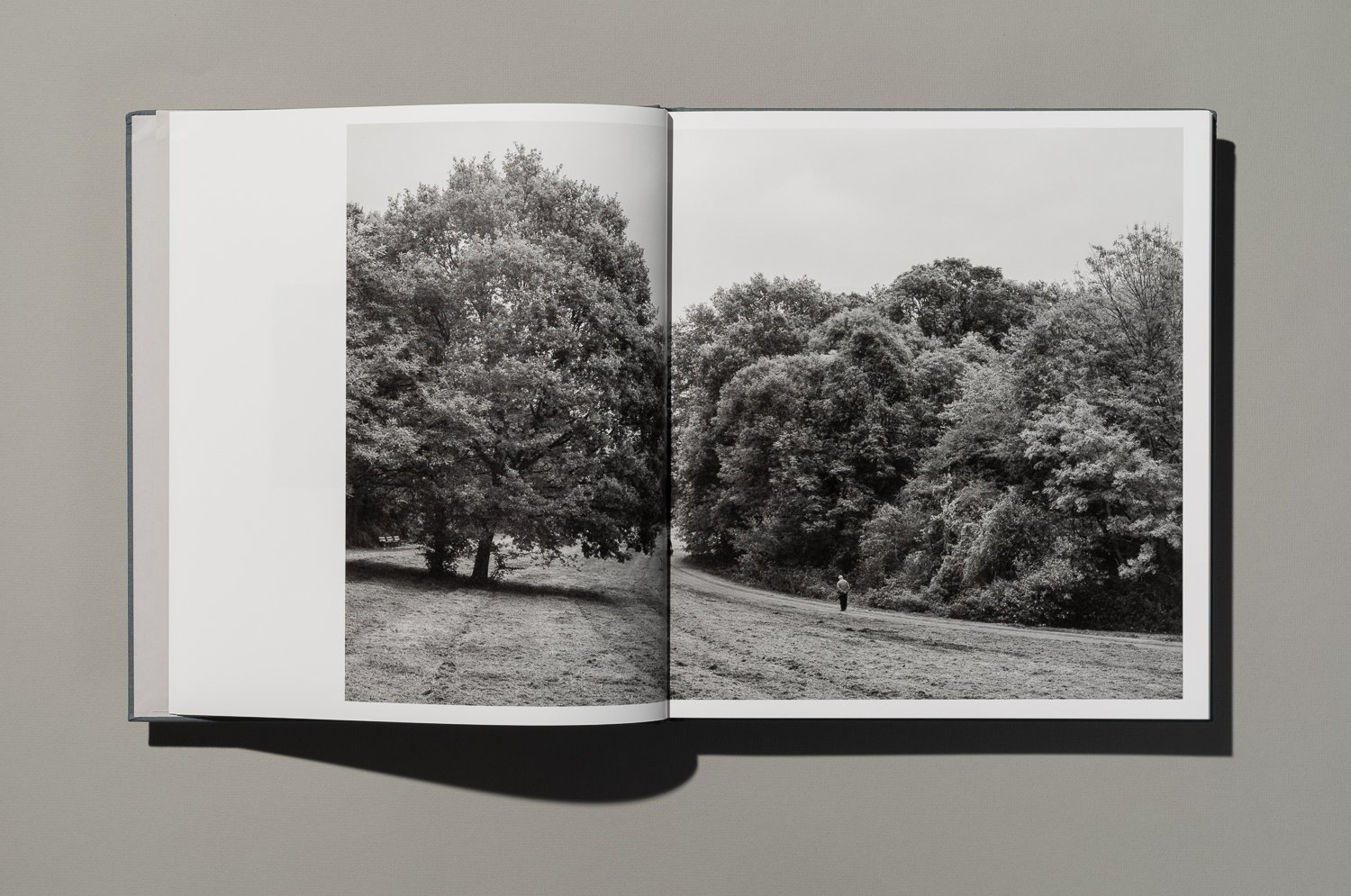

Erde, Feuer, Wind, Wasser (Earth, Fire, Wind, Water) is the result of a long-term documentary project. The four-volume publication raises questions about cultural and collective heritage, taking the viewer on a (visual) journey through the story of 20th- and 21st-century Europe – a story of war, migration and political upheaval, a story that has had a profound impact on unnumbered families.

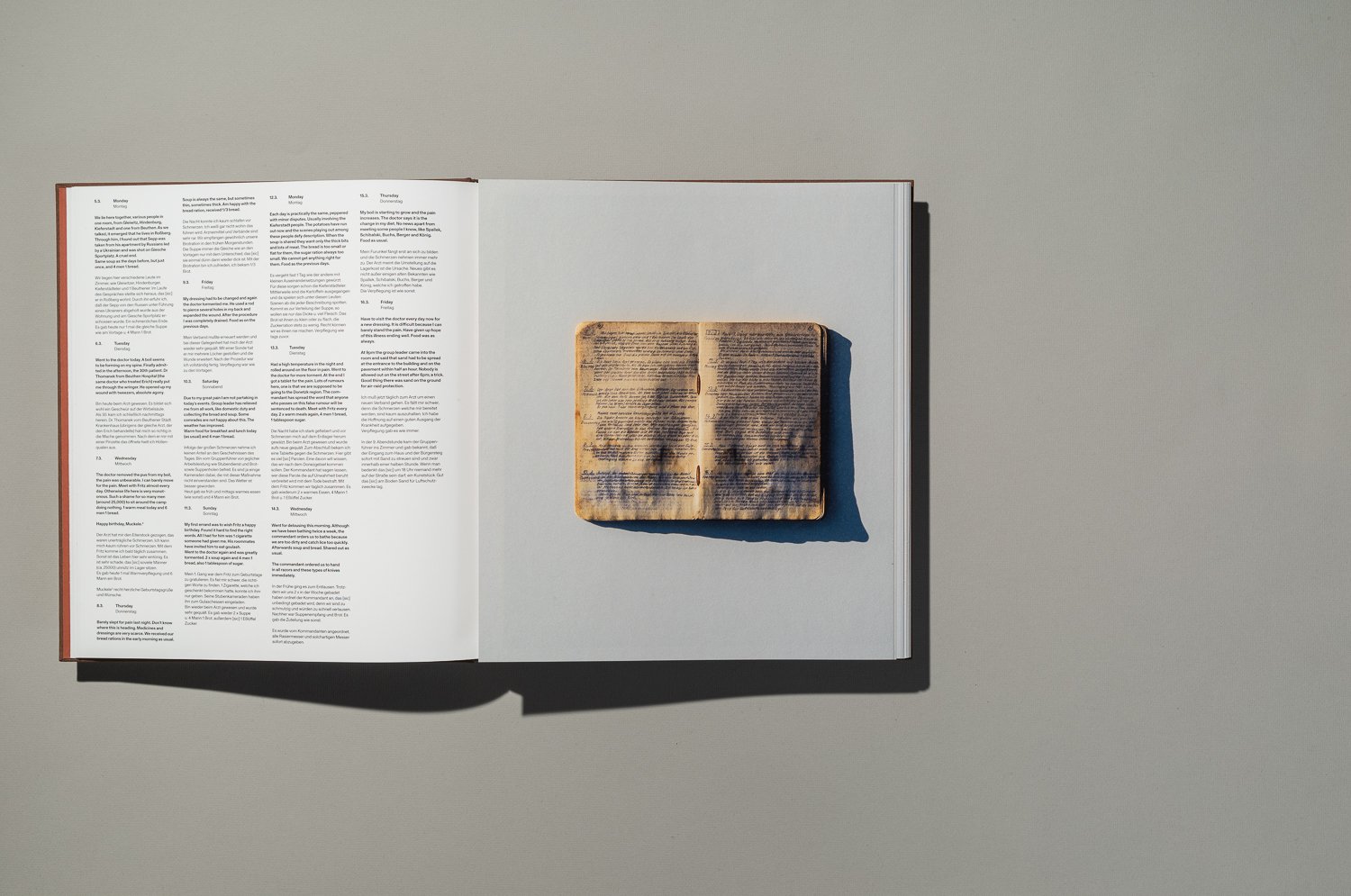

In each book – symbolically anchored in the four elements and the four seasons, emphasising the cycle of life – the narrative focuses on various generations of my family over the last 75 years. It begins with my grandfather’s diary (a historical fragment from his time as a prisoner of war in Ukraine), moves on to the family’s emigration from Poland to West Germany in the 1970s and the world in which the

Polish relatives live today, before exploring his relationship with my widowed father in Germany and my own search for identity in Norway, his adopted home.

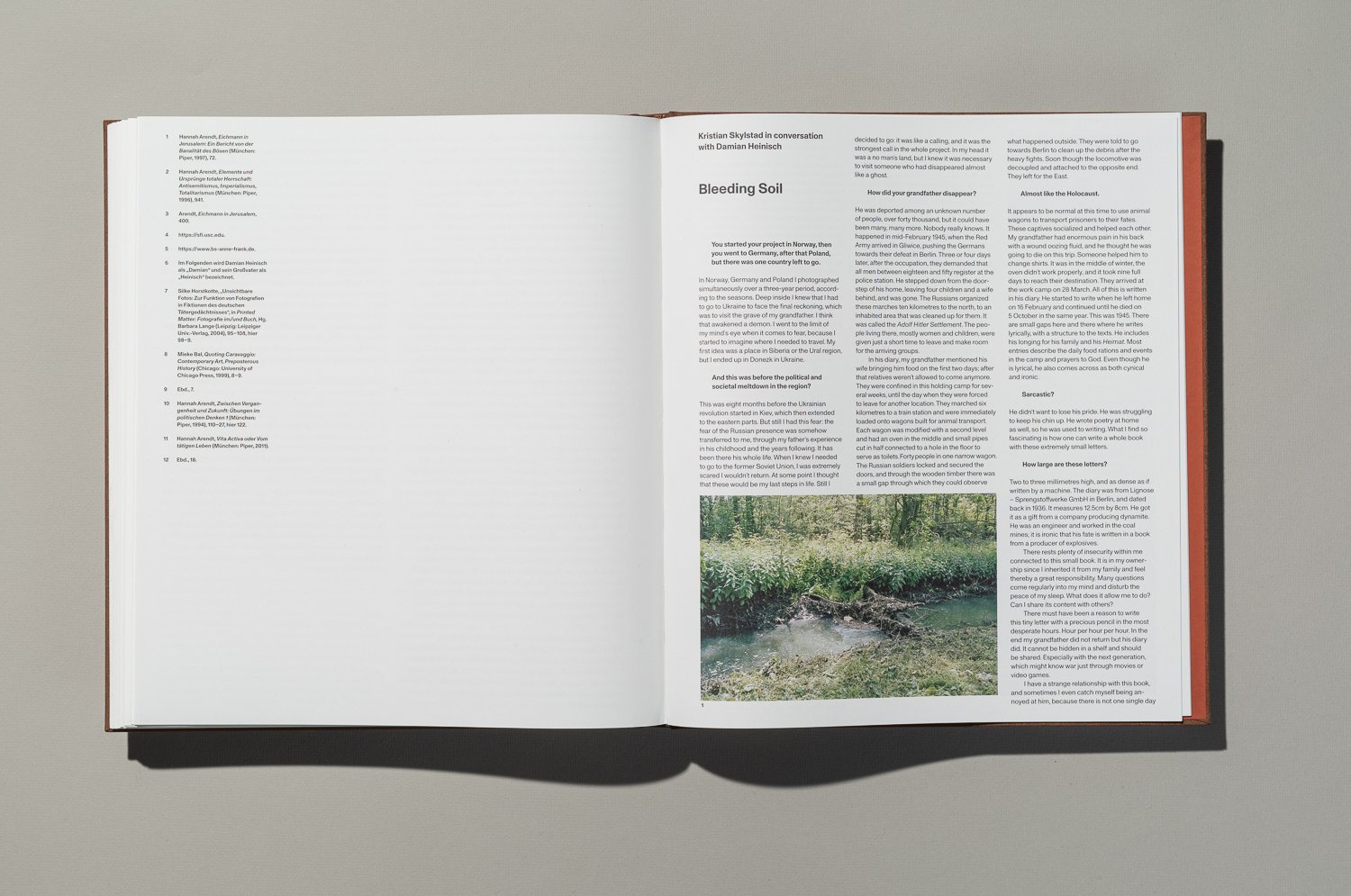

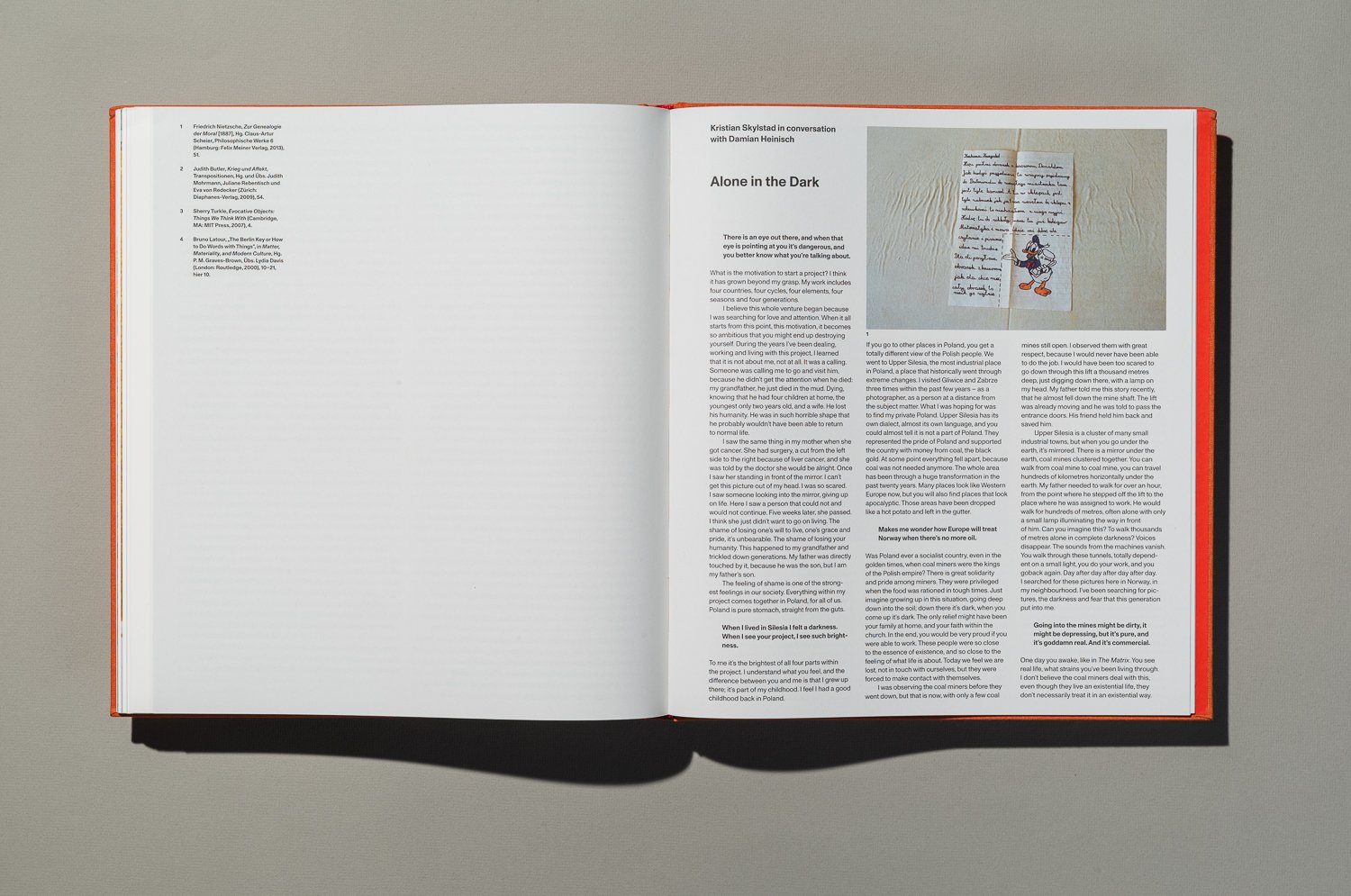

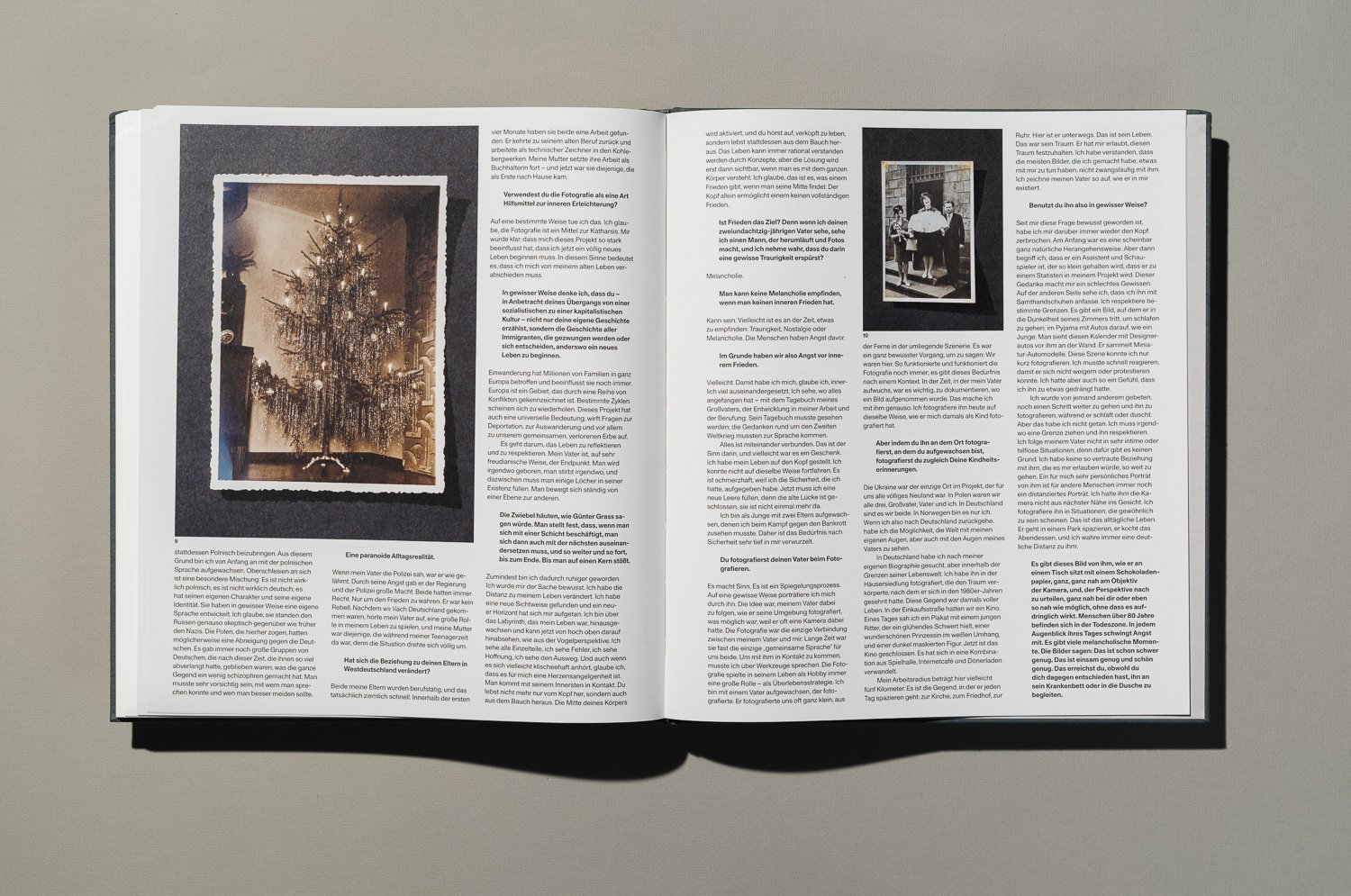

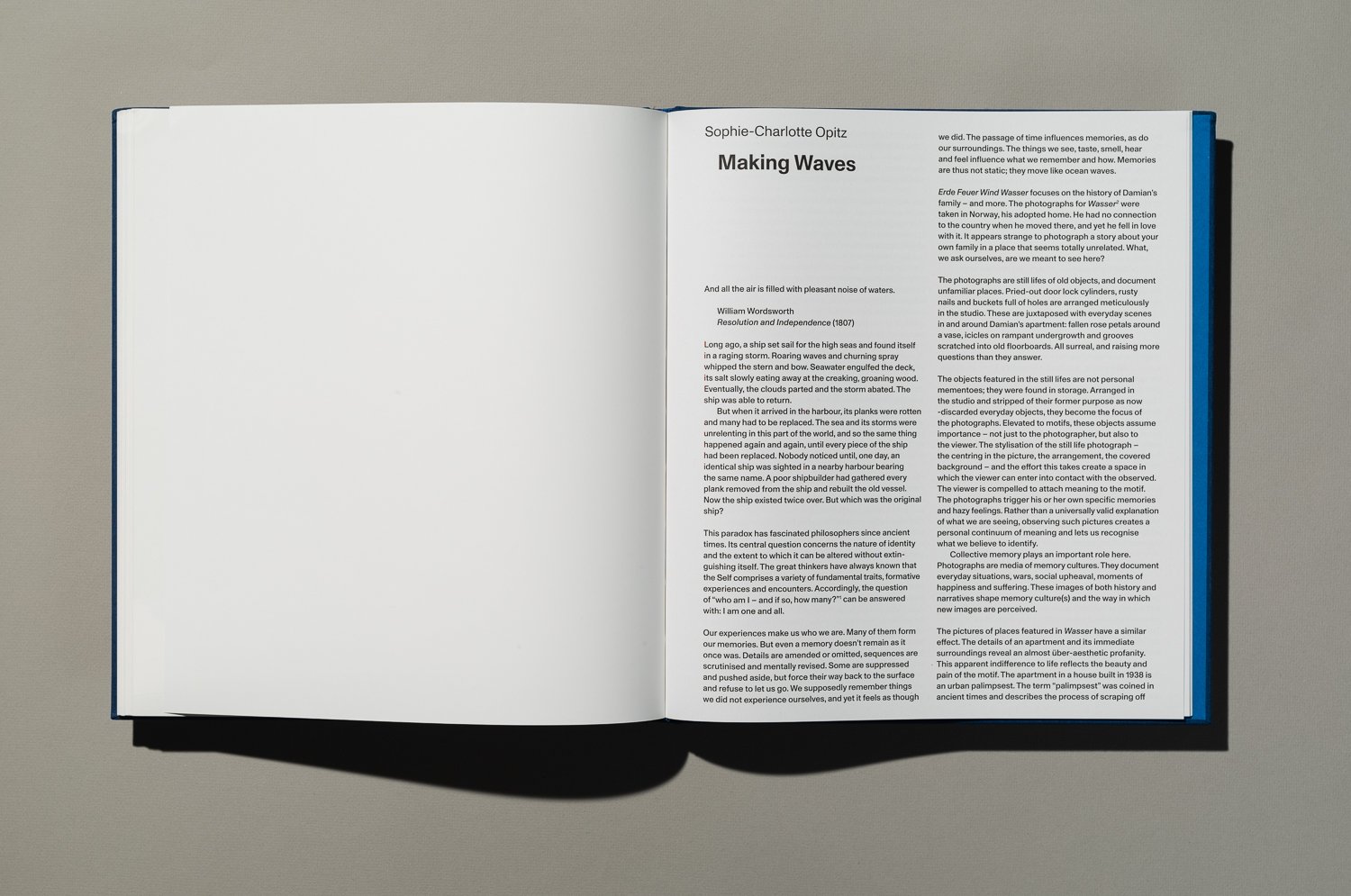

Each of the four books is accompanied by texts by the media and art scholar Sophie-Charlotte Opitz, who critically examines photography’s mechanisms of action and places Heinisch’s project in an overall cultural-historical context. With the four volumes, Opitz also negotiates the various workings and dynamics of cultures of memory that operate across national borders and generations. Interviews conducted by Kristian Skylstad complement the publication, which also portrays a precarious universal and current history in a personal way.

This book is designed by Andreas Skilhagen and published by Kehrer Verlag in Heidelberg in a limited, numbered and signed edition of 600 copies. It can be acquired here.

The 4 book have been launched at Noplace in Oslo in October 2021.

Read about the project at:

LFI - Leica Fotografi International

A conversation about the project led by Brad Feuerhelm has also been published on “Nearest Truth”.

It can also be found in the archive of the Virtual Shelf.

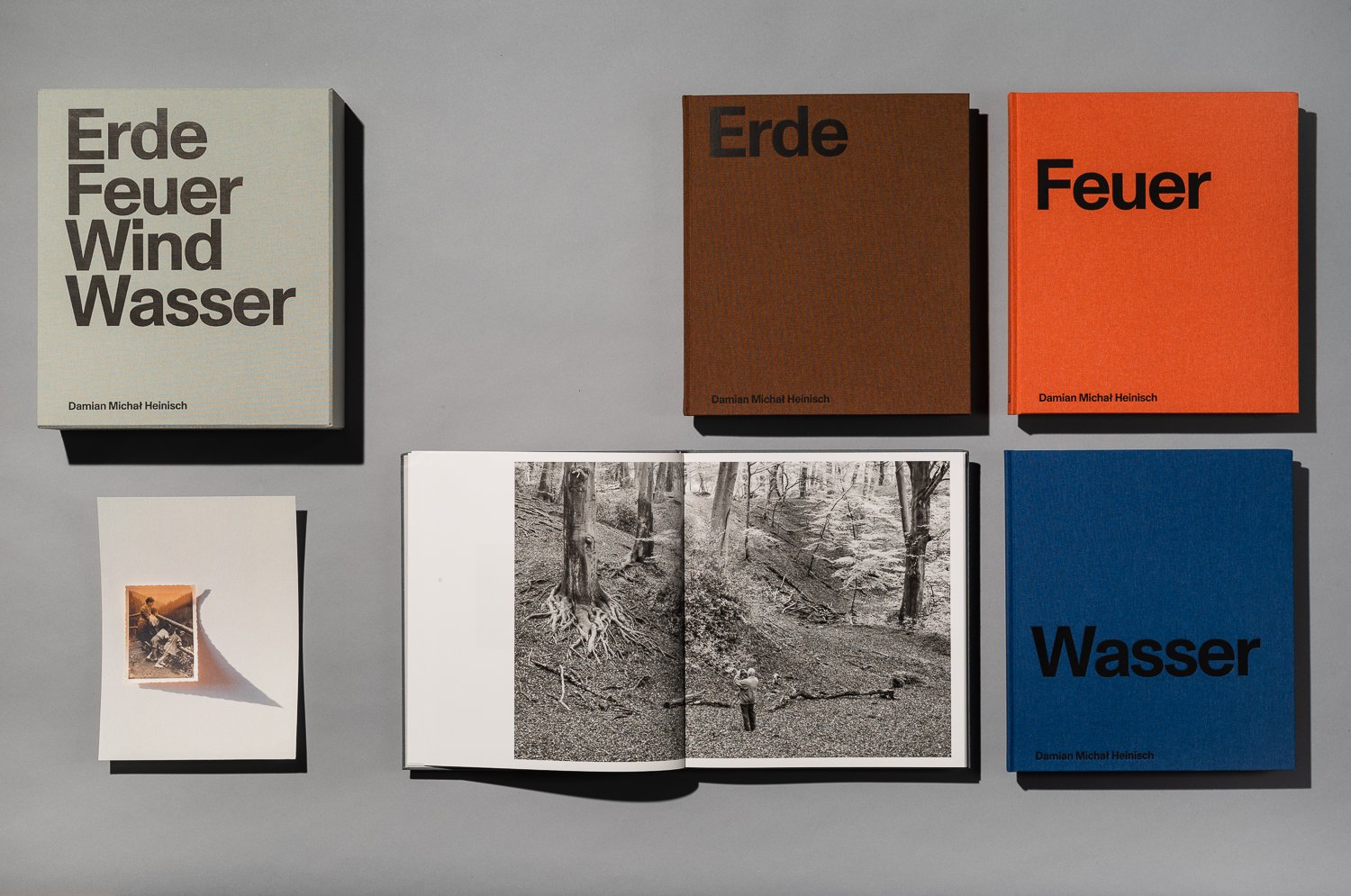

erde

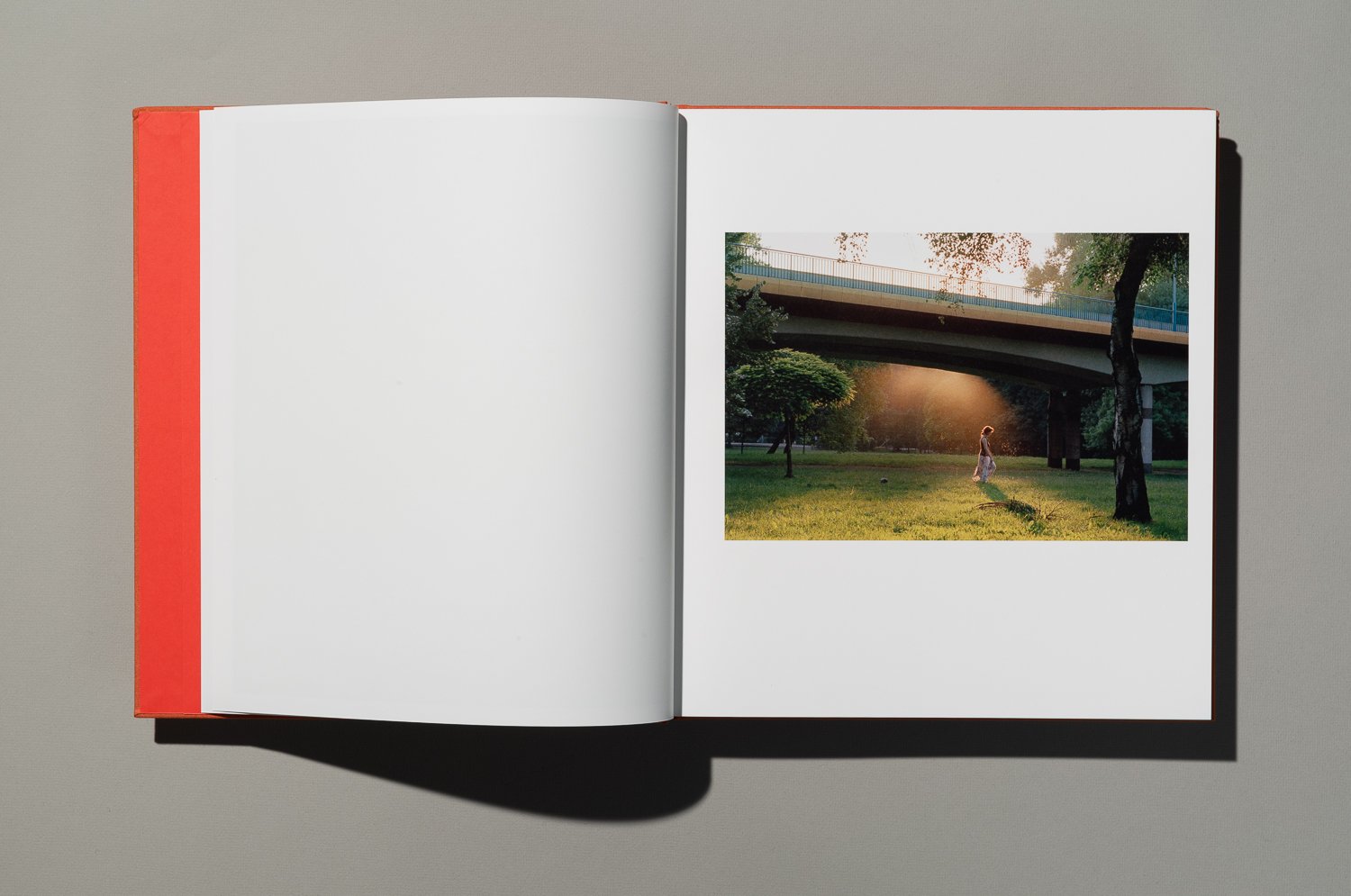

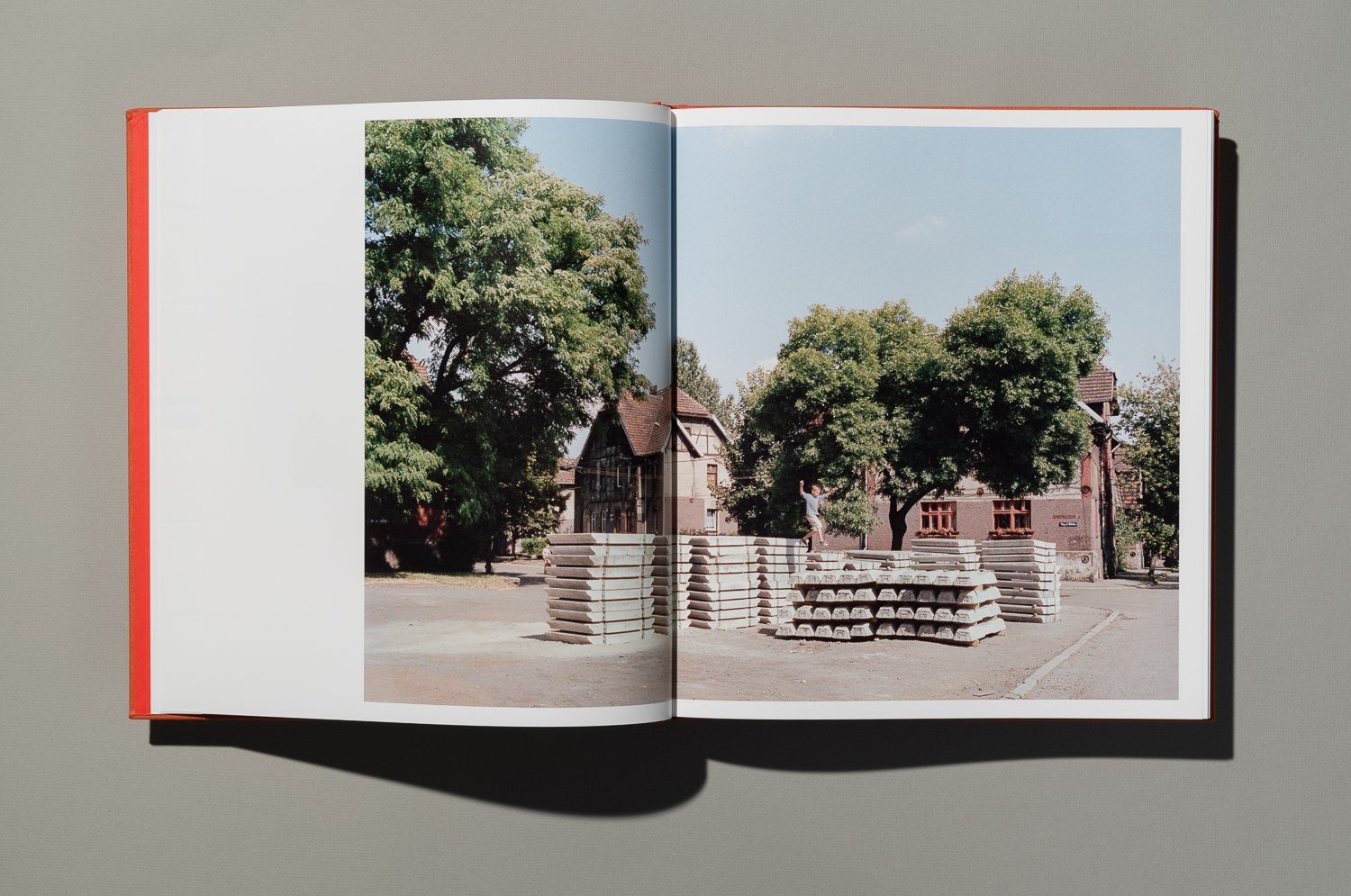

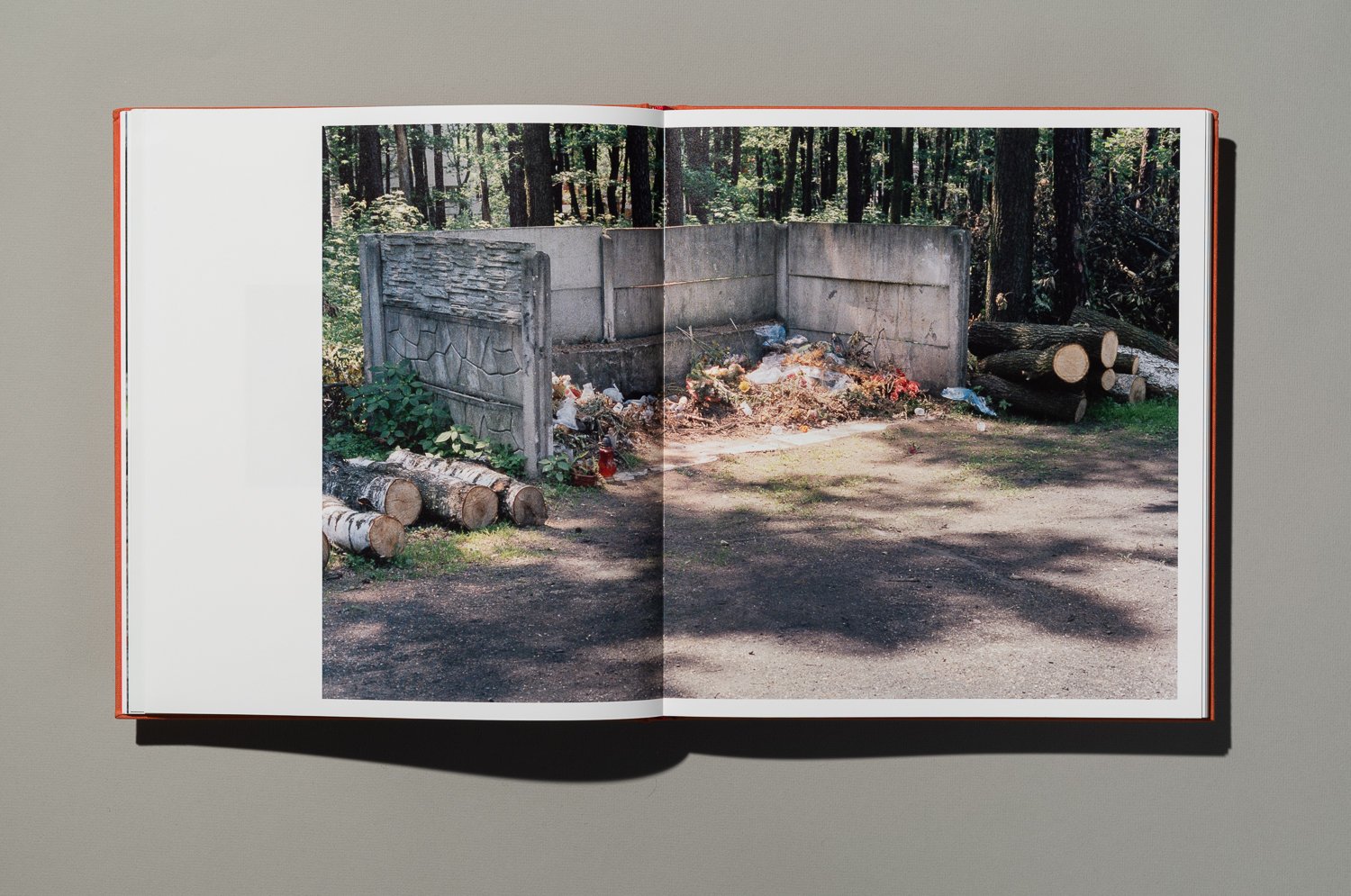

We are living in times of change and it is more urgent than ever that we discuss how to deal with the past. Erde is an example of the impulse to act. It encourages us to think and to remember, to interact with one another and to discuss the history in which we have been raised and live. Our constant interaction with the past is the foundation for a living collective memory in which memories can circulate, dynamic and constantly evolving. There is, of course, no

way of knowing what the future will bring. But we need to recognise the potential of this situation. We can resist the repetition of a past that must never be allowed to happen again. We can fill our everyday lives with values that render evil pointless. We can live the past as part of our reality and, ultimately, begin something new.

Excerpt from the essay by Sophie-Charlotte Opitz.

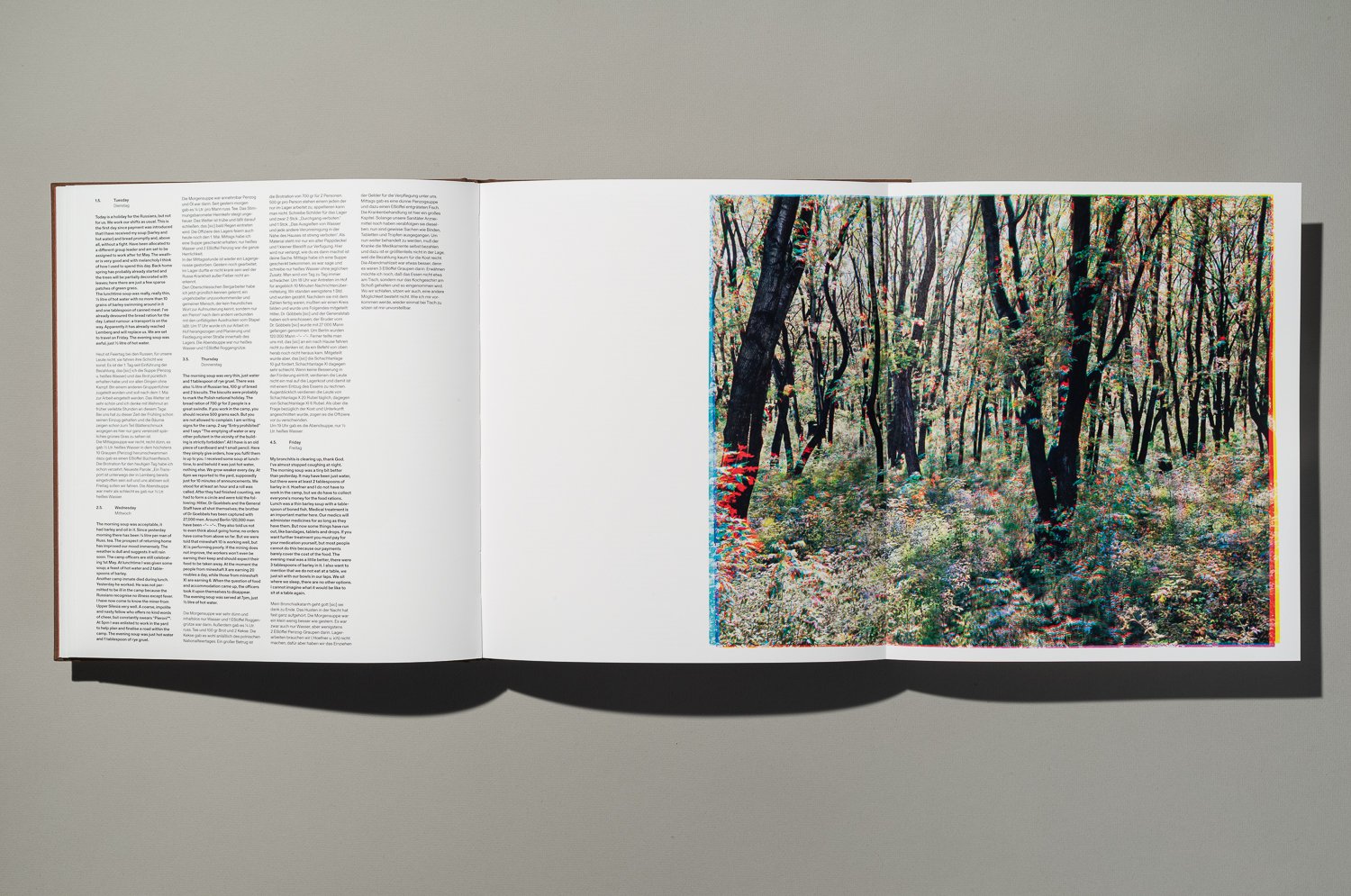

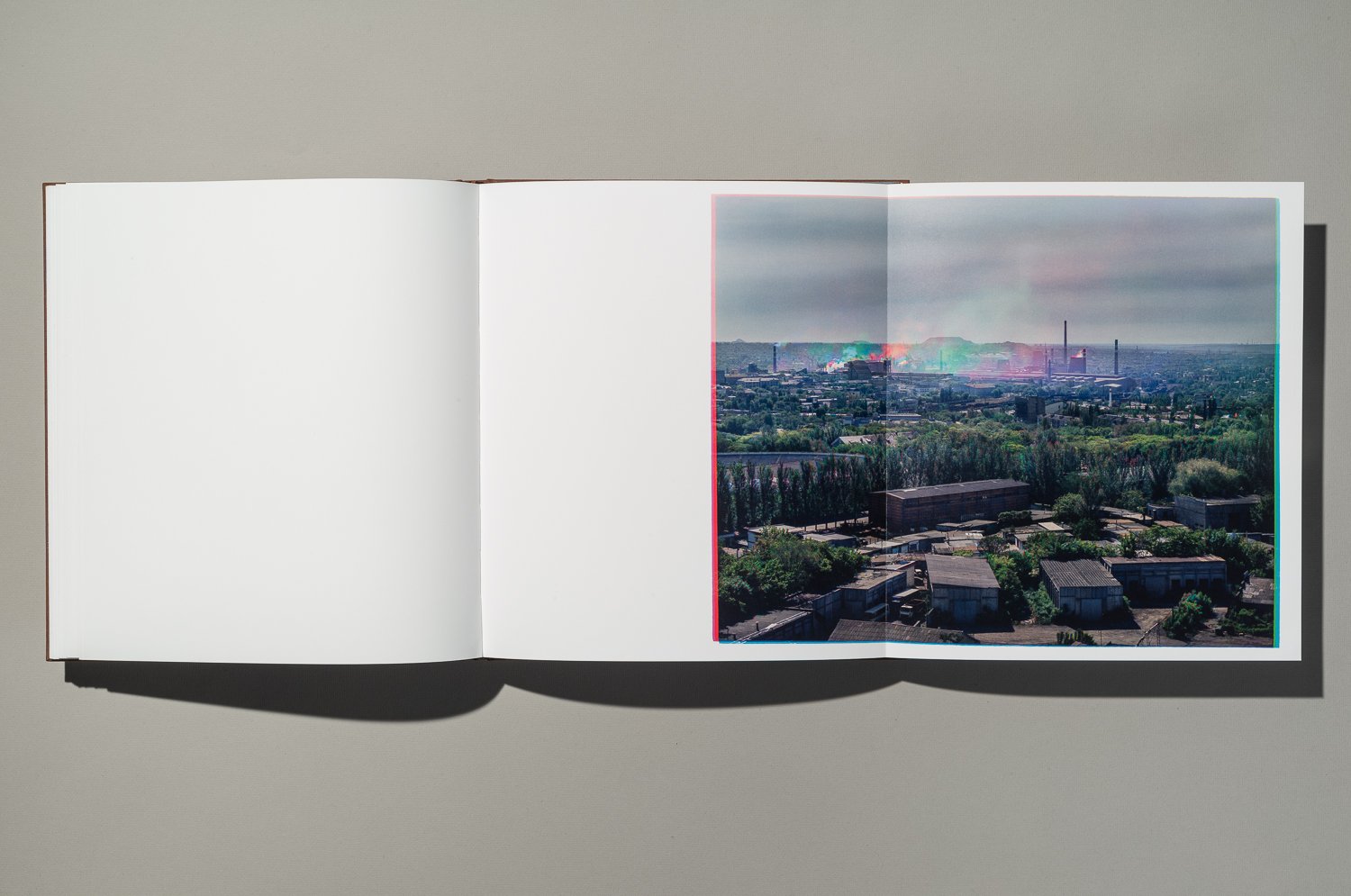

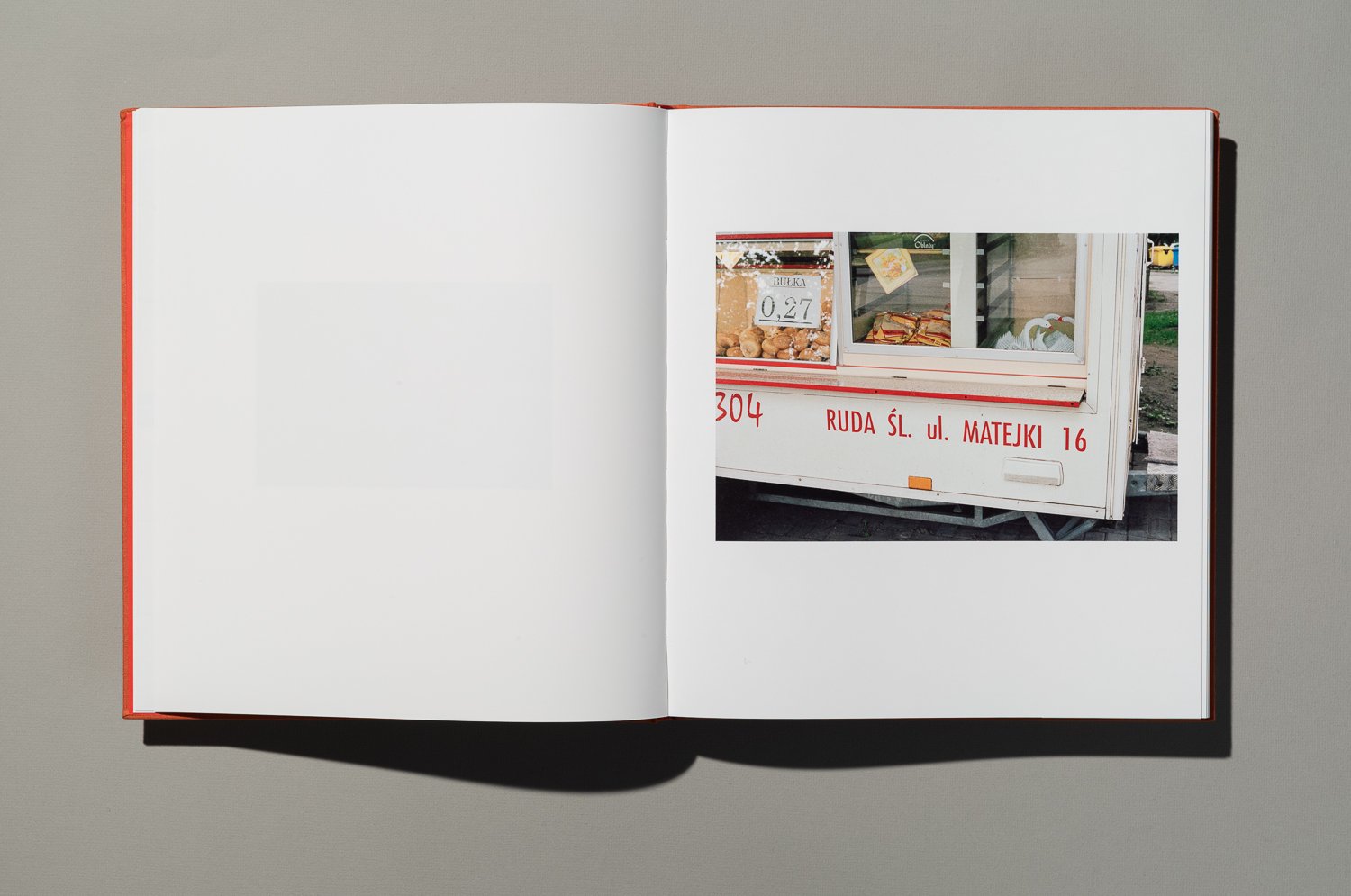

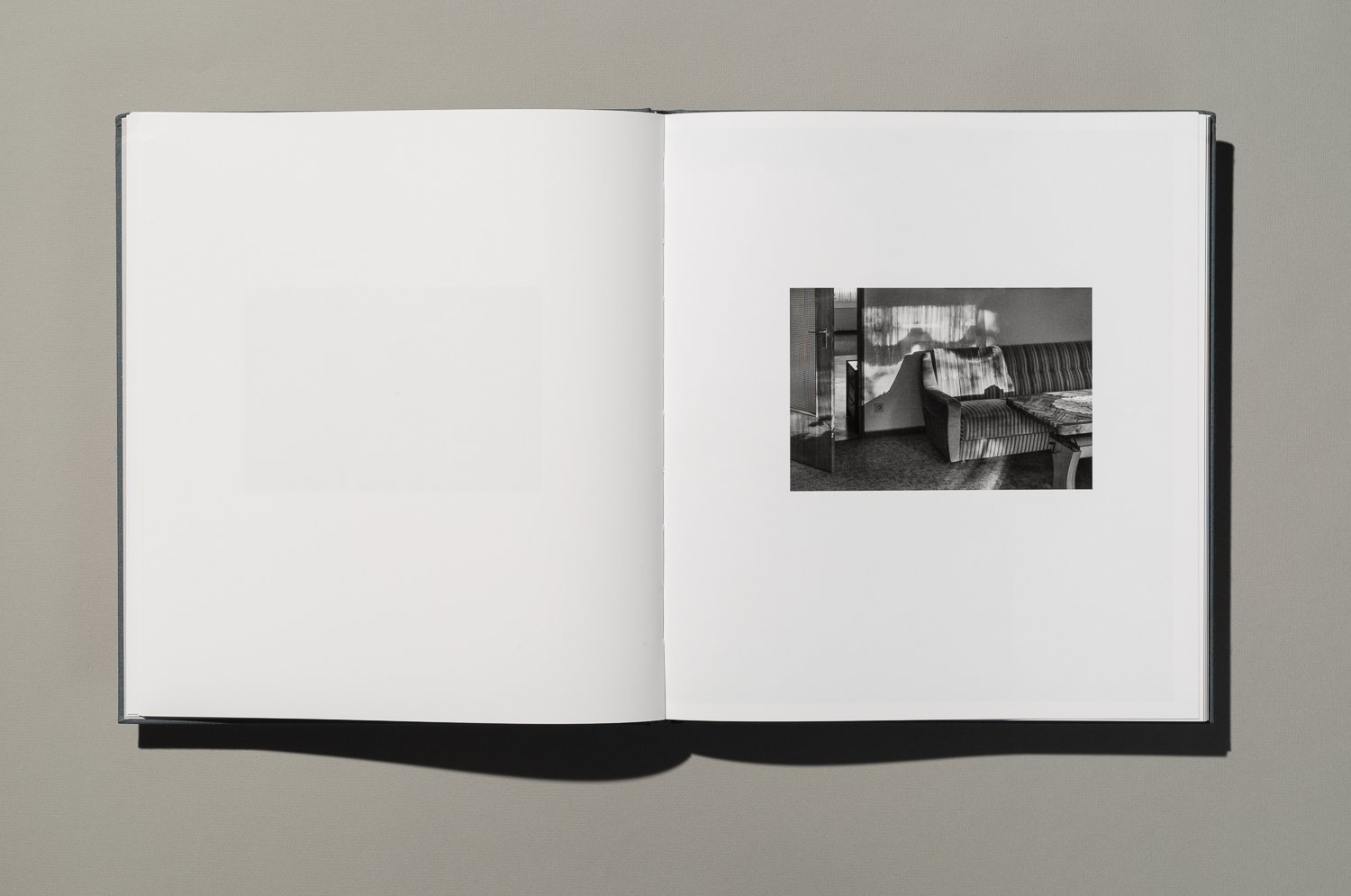

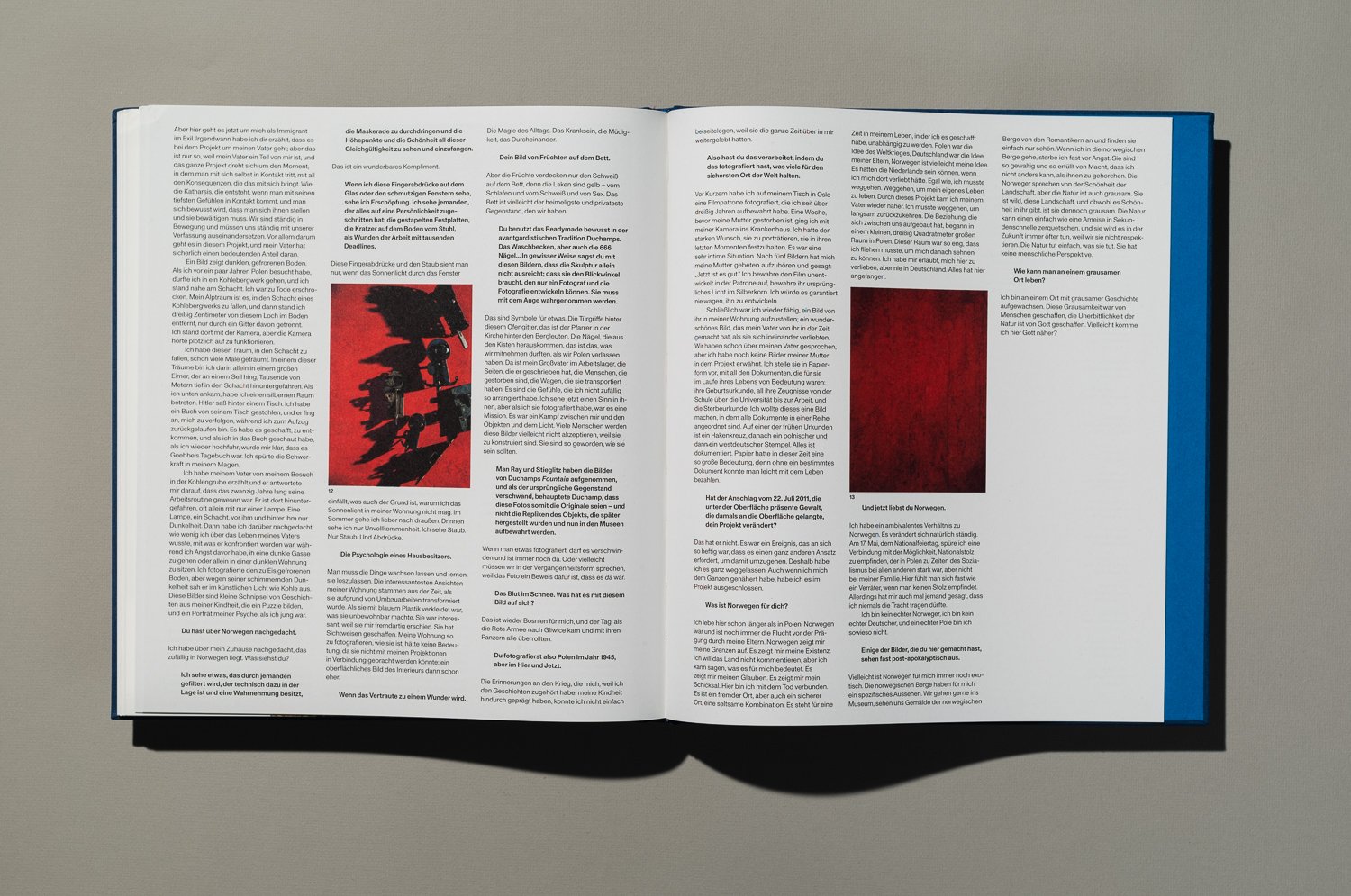

feuer

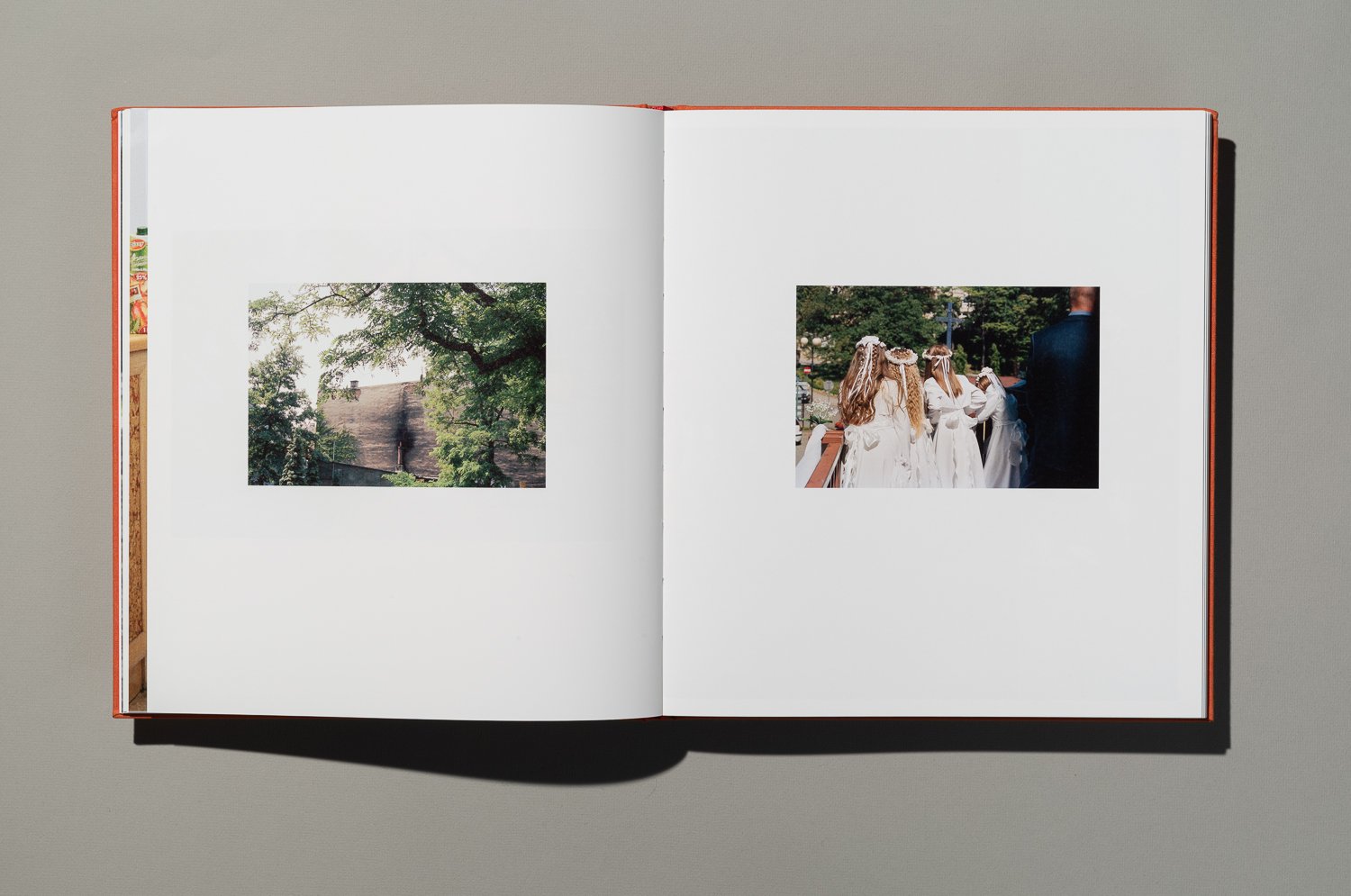

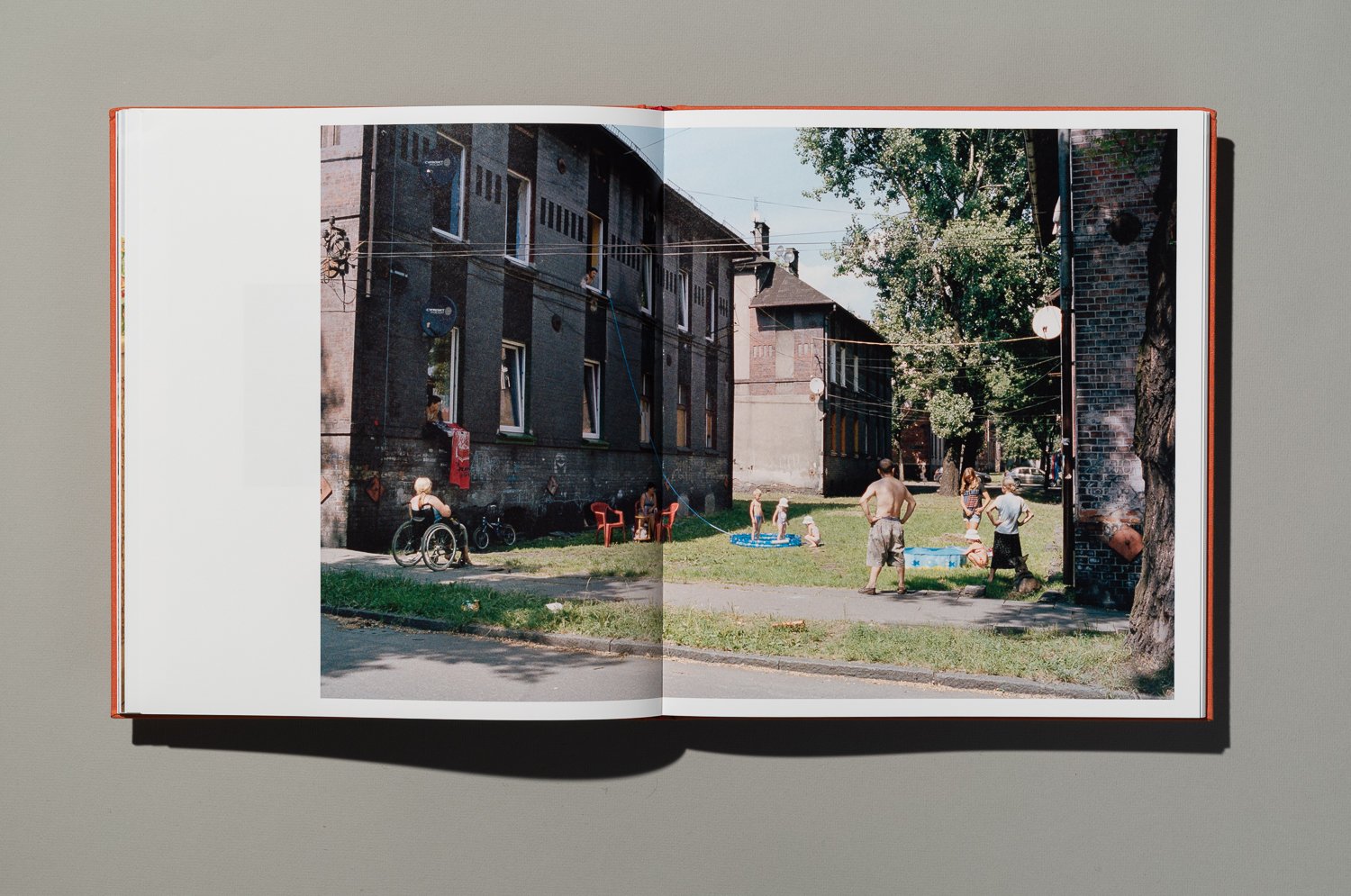

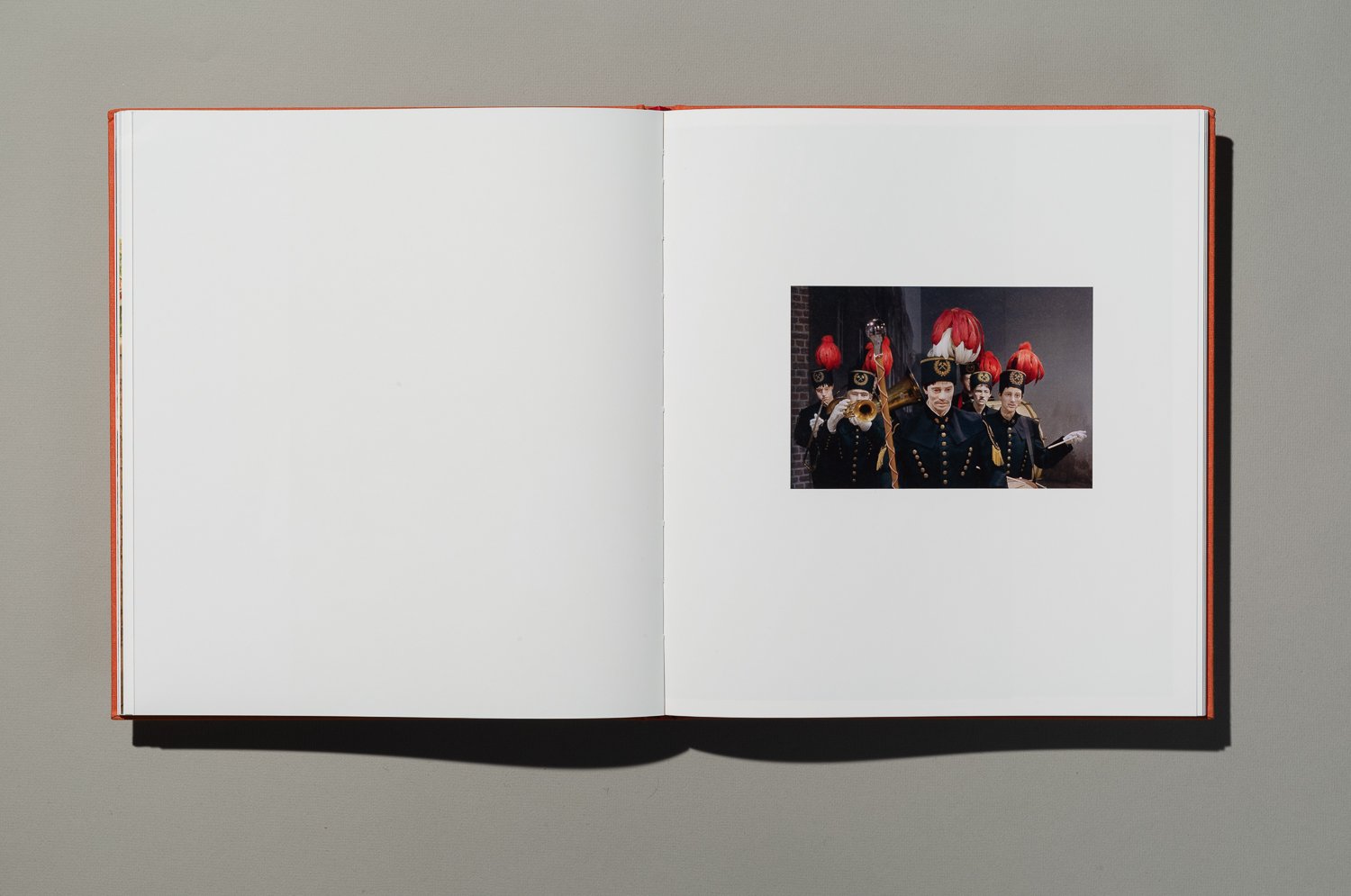

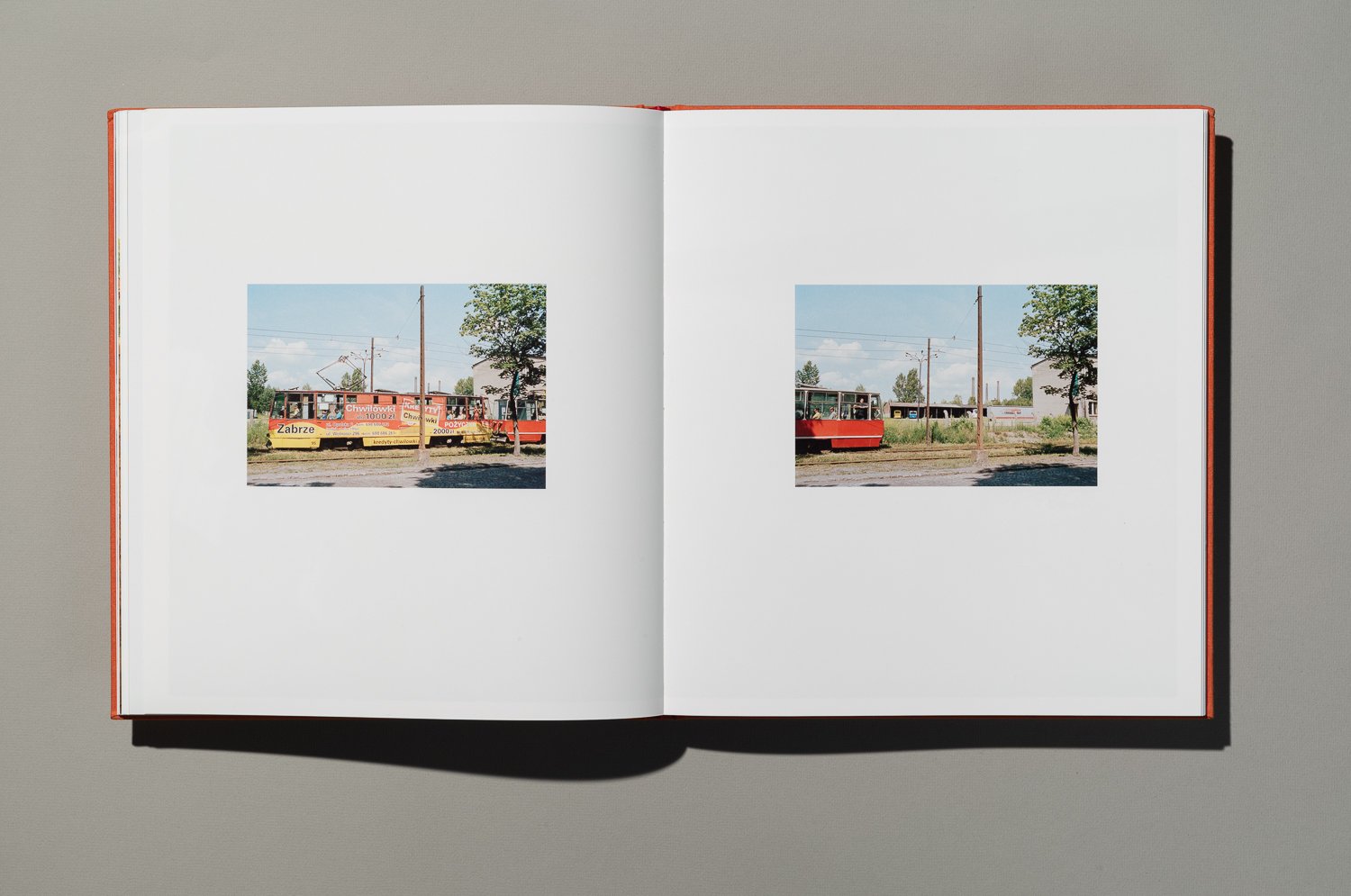

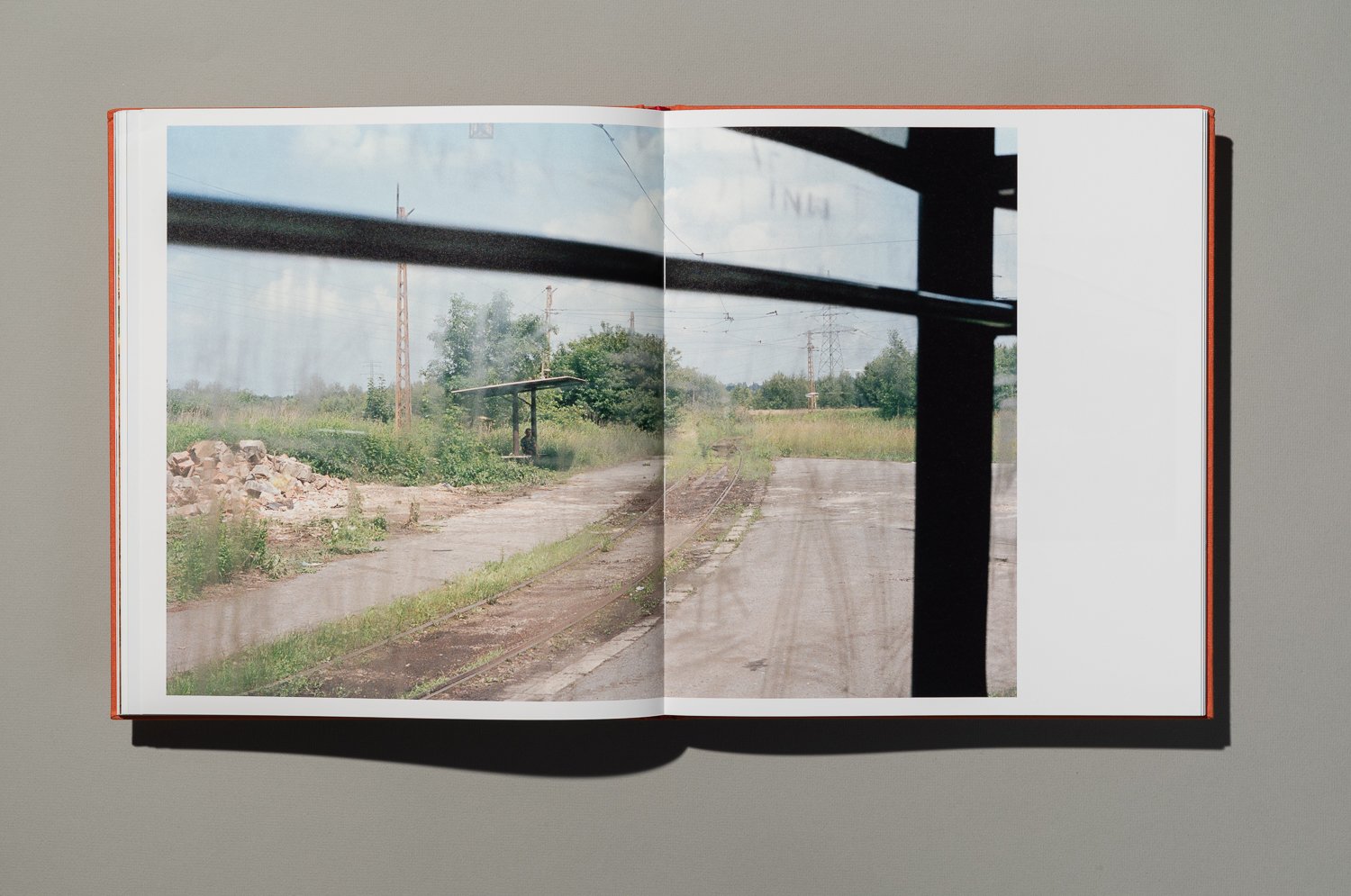

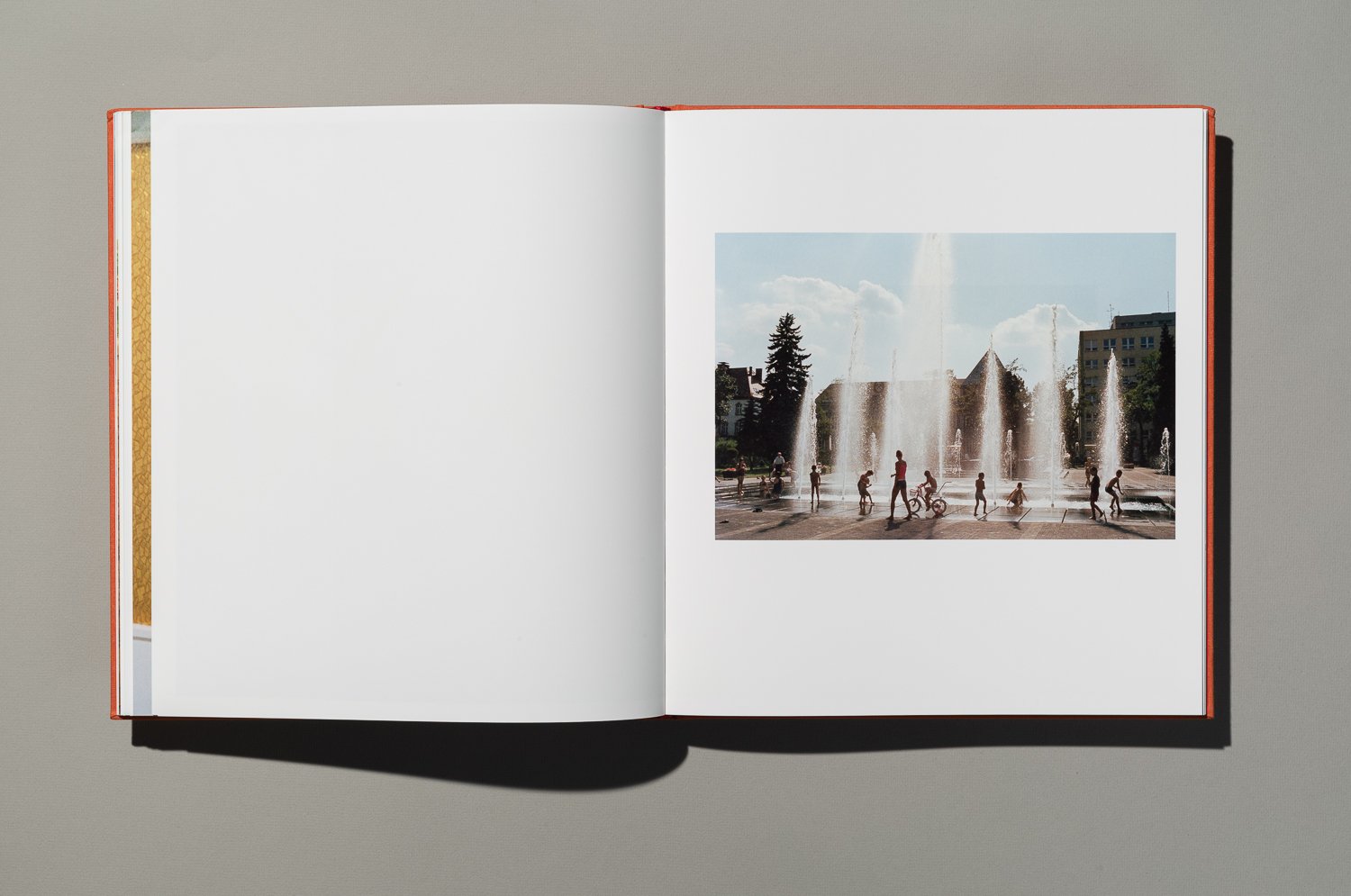

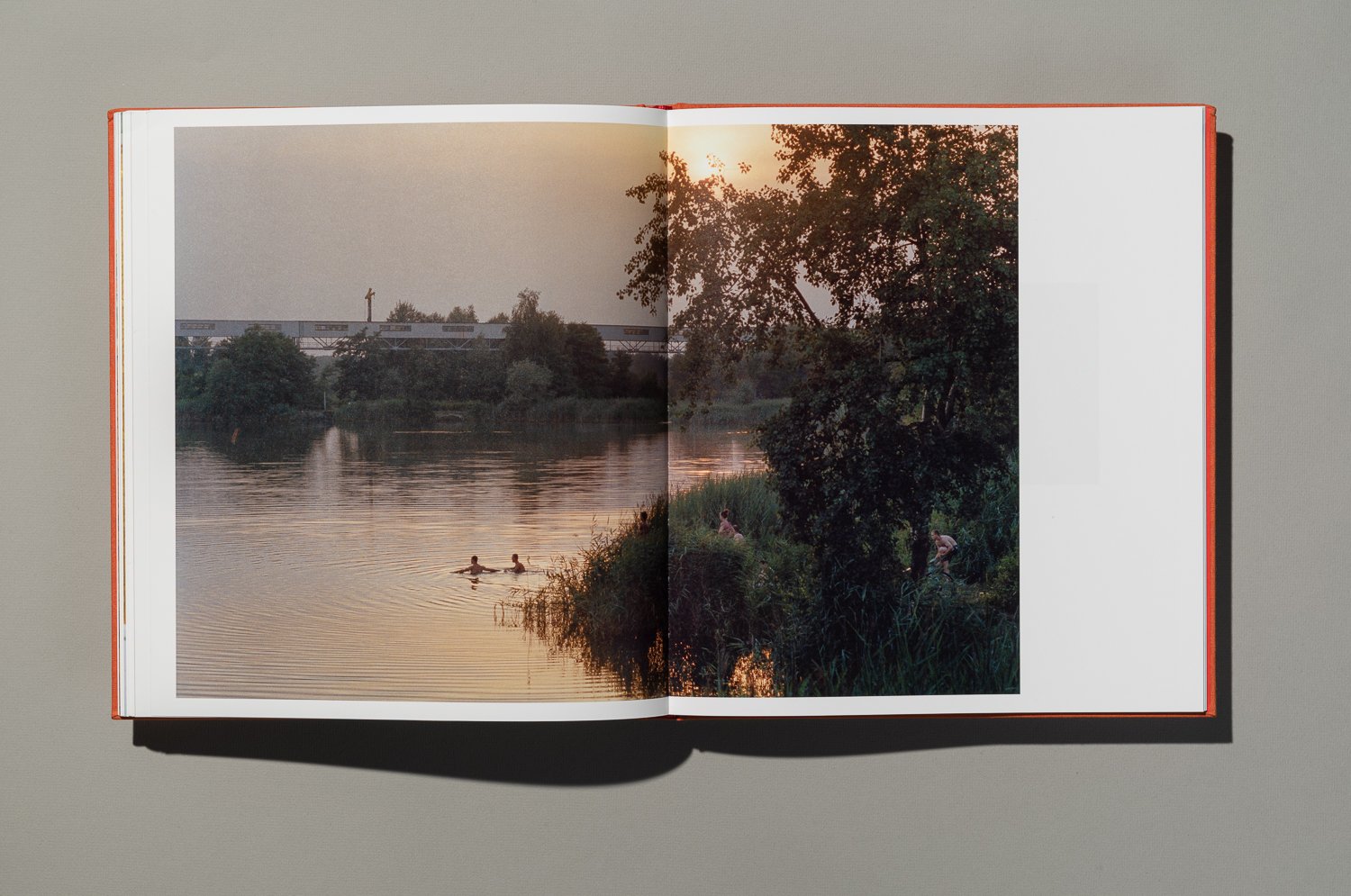

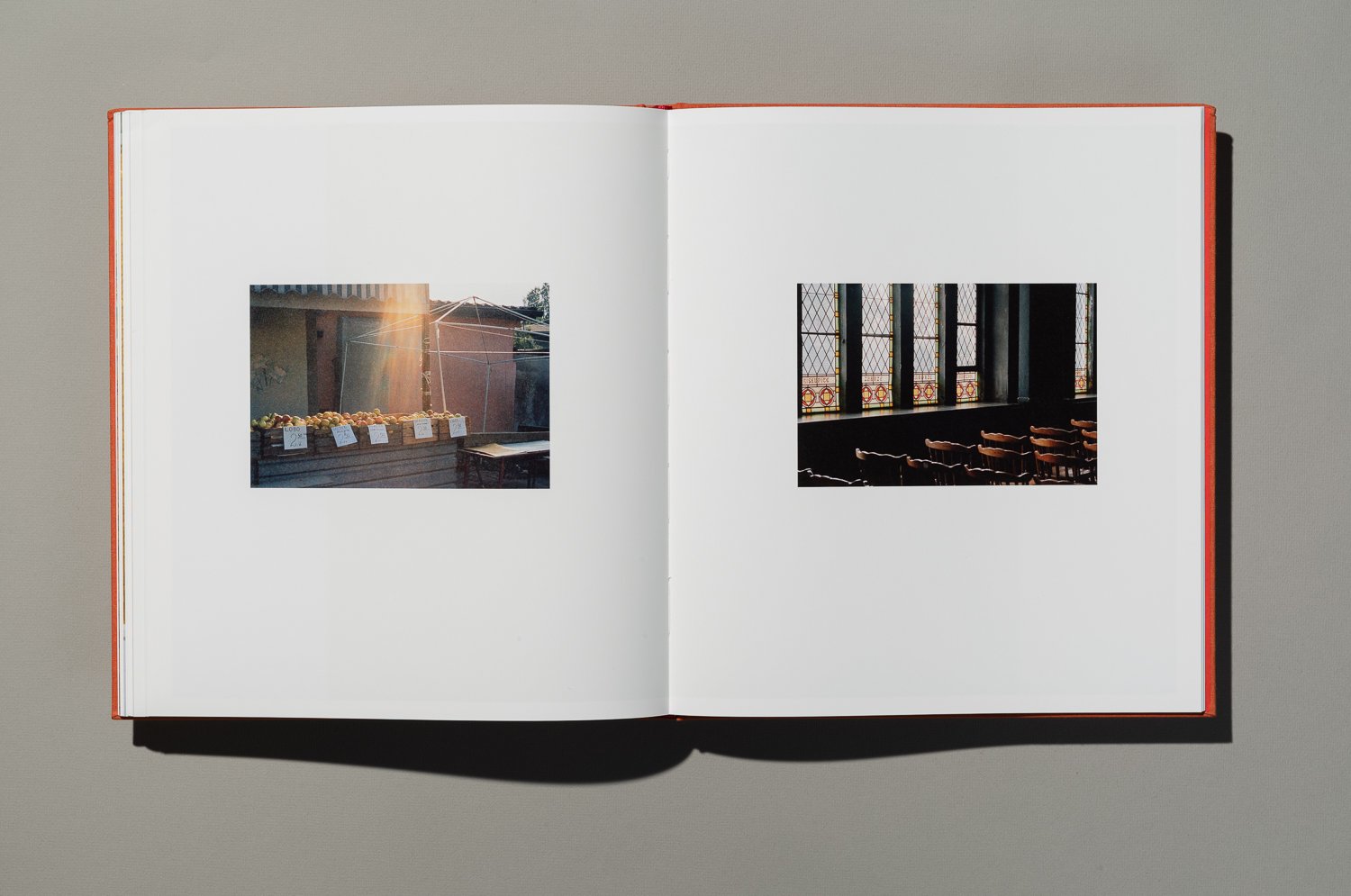

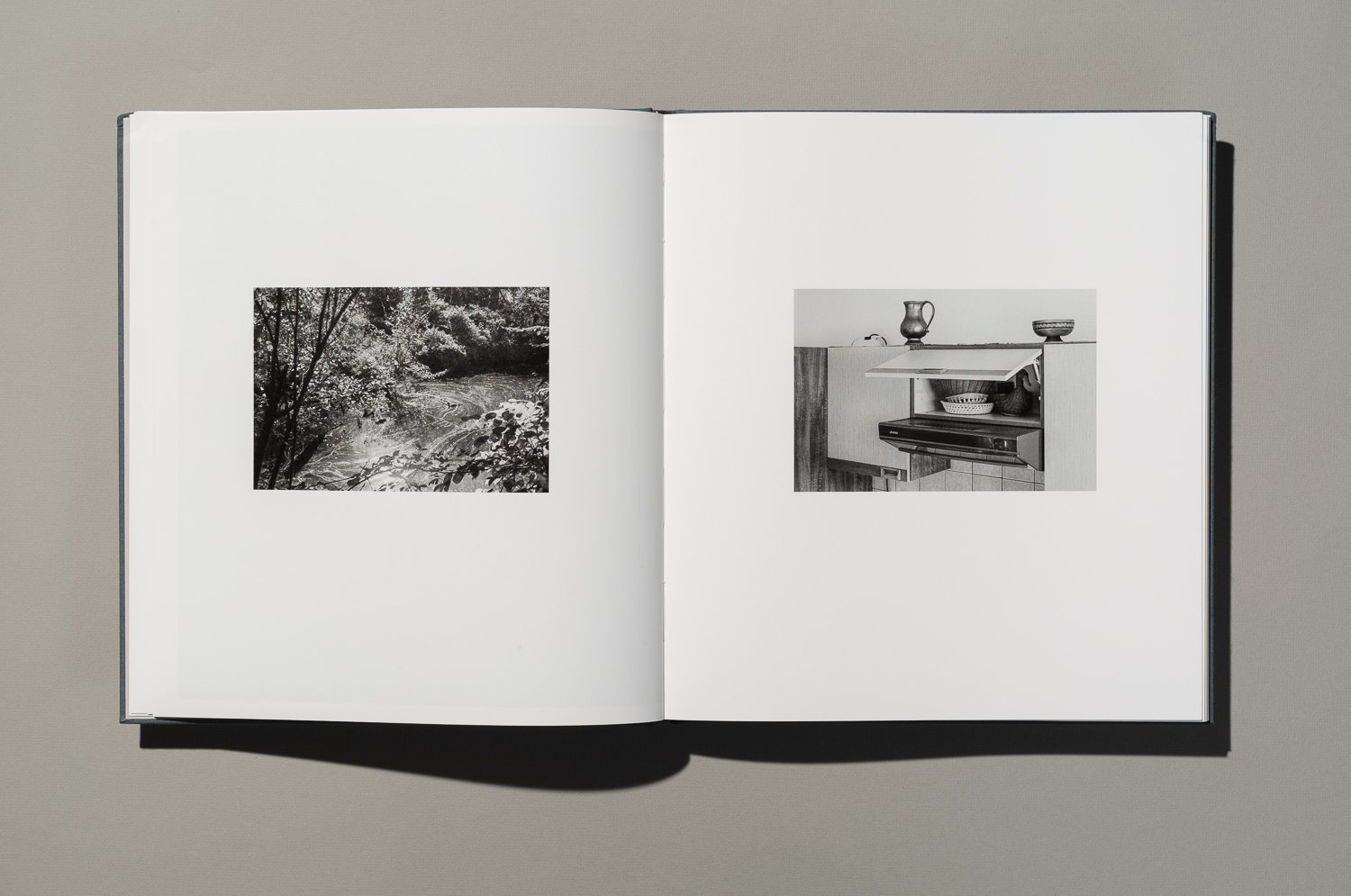

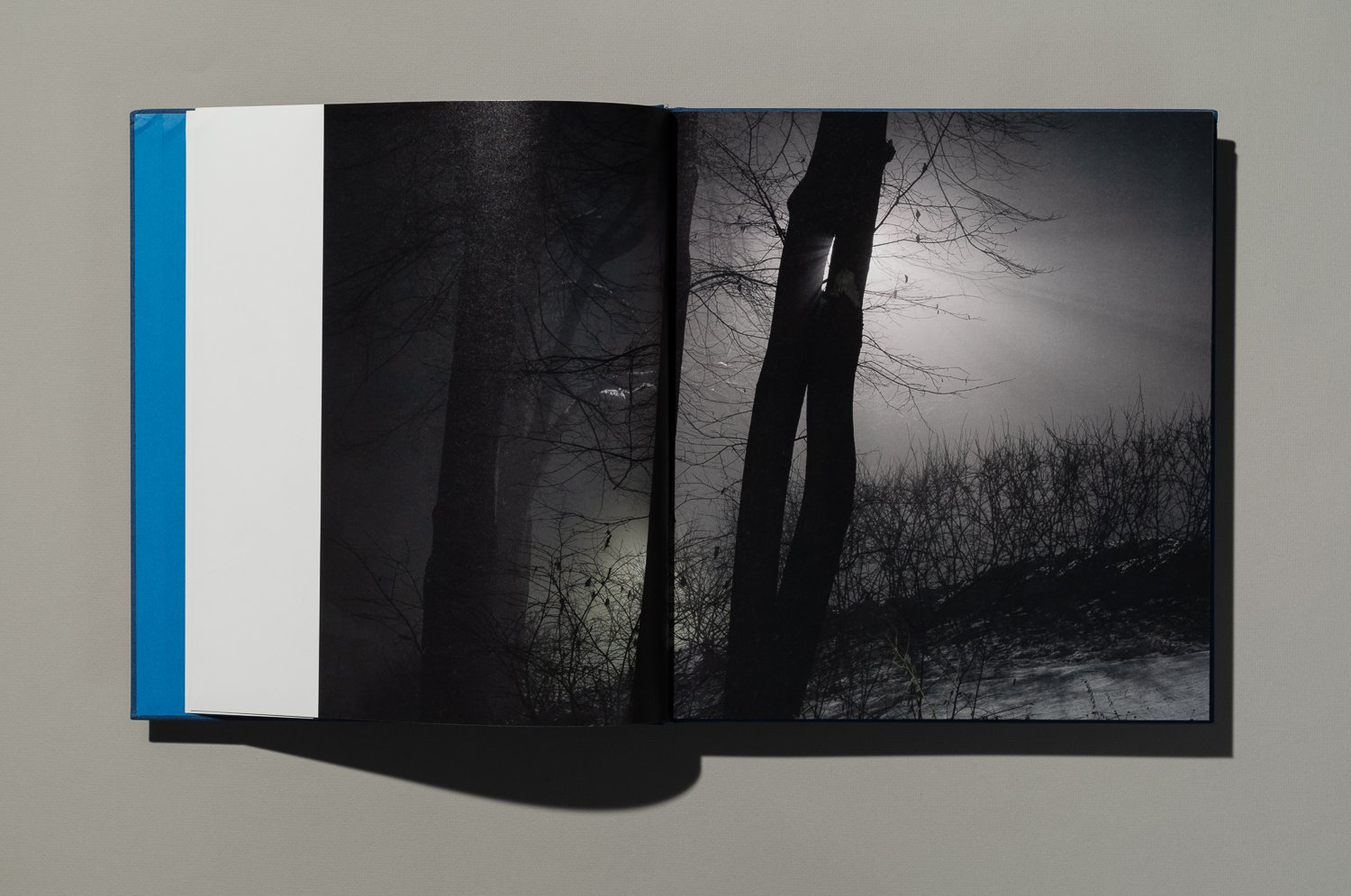

In Feuer, photographs are conceived and arranged in such a way as to slow down the pace of viewing. Various methods are employed ad hoc: some of them look like hidden picture puzzles; there is so much to discover that you never tire of looking. Others are arranged together across double pages to create a dialogue with one another. The children in one photograph appear to look beyond the frame at the family scene on the opposite page. Other

photographs are enveloped in a mystical stillness; their aesthetic precision leaves you asking what has happened –or what is yet to happen? Slowing down the gaze creates a space for thoughts. The visible connects with visibilities. Displaying the various motifs implies that they necessarily belong together.

Excerpt from the essay by Sophie-Charlotte Opitz.

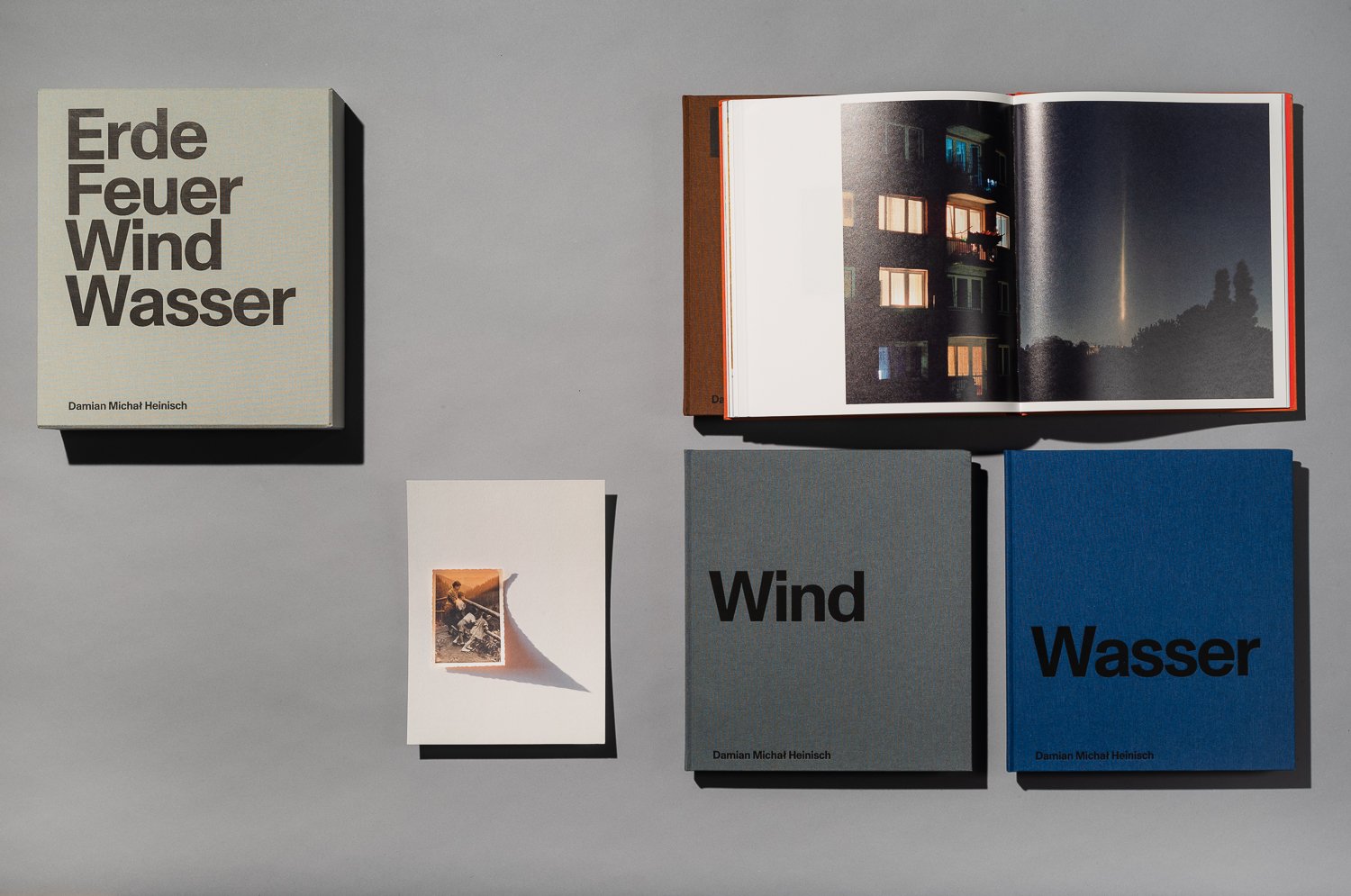

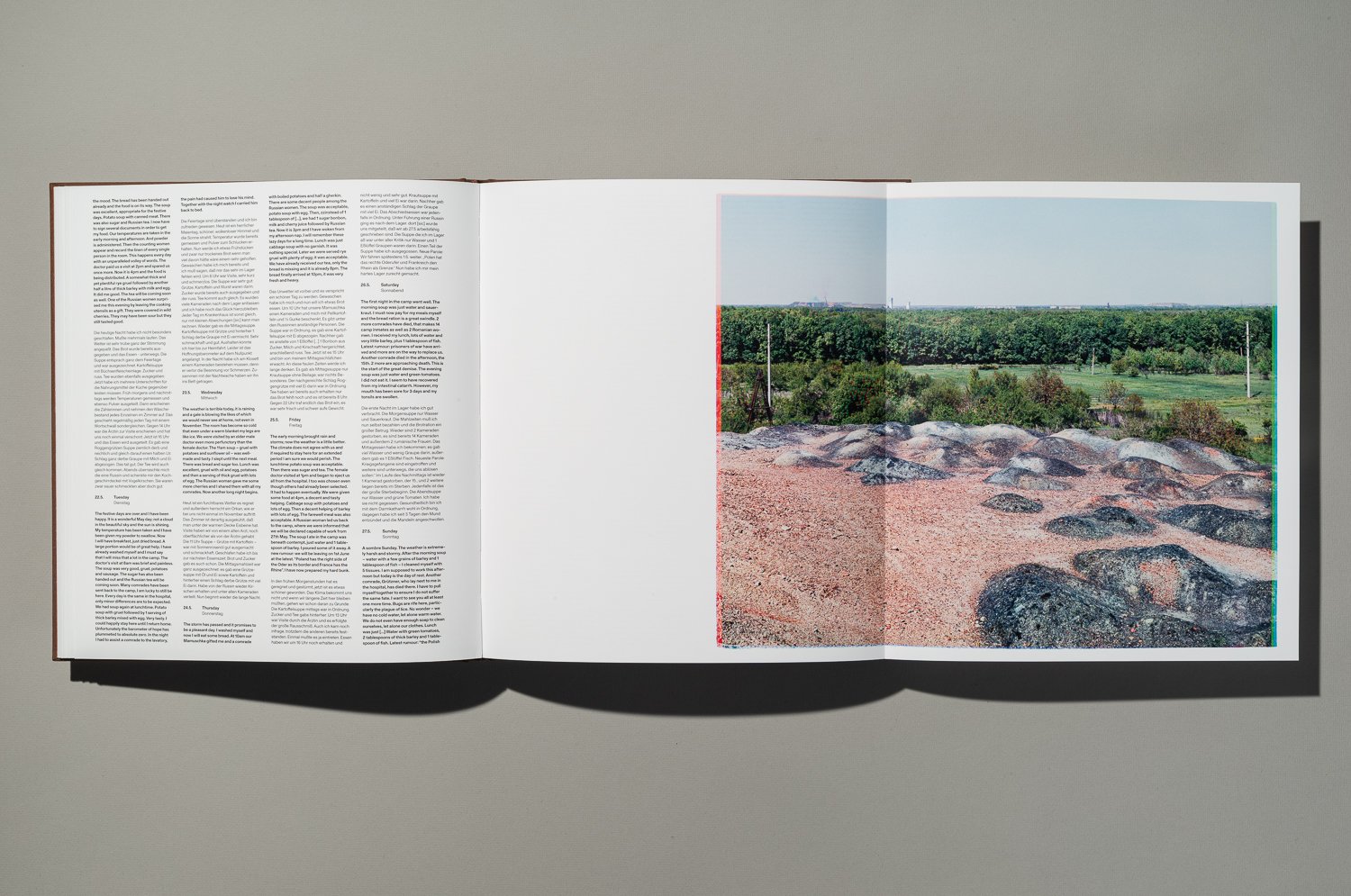

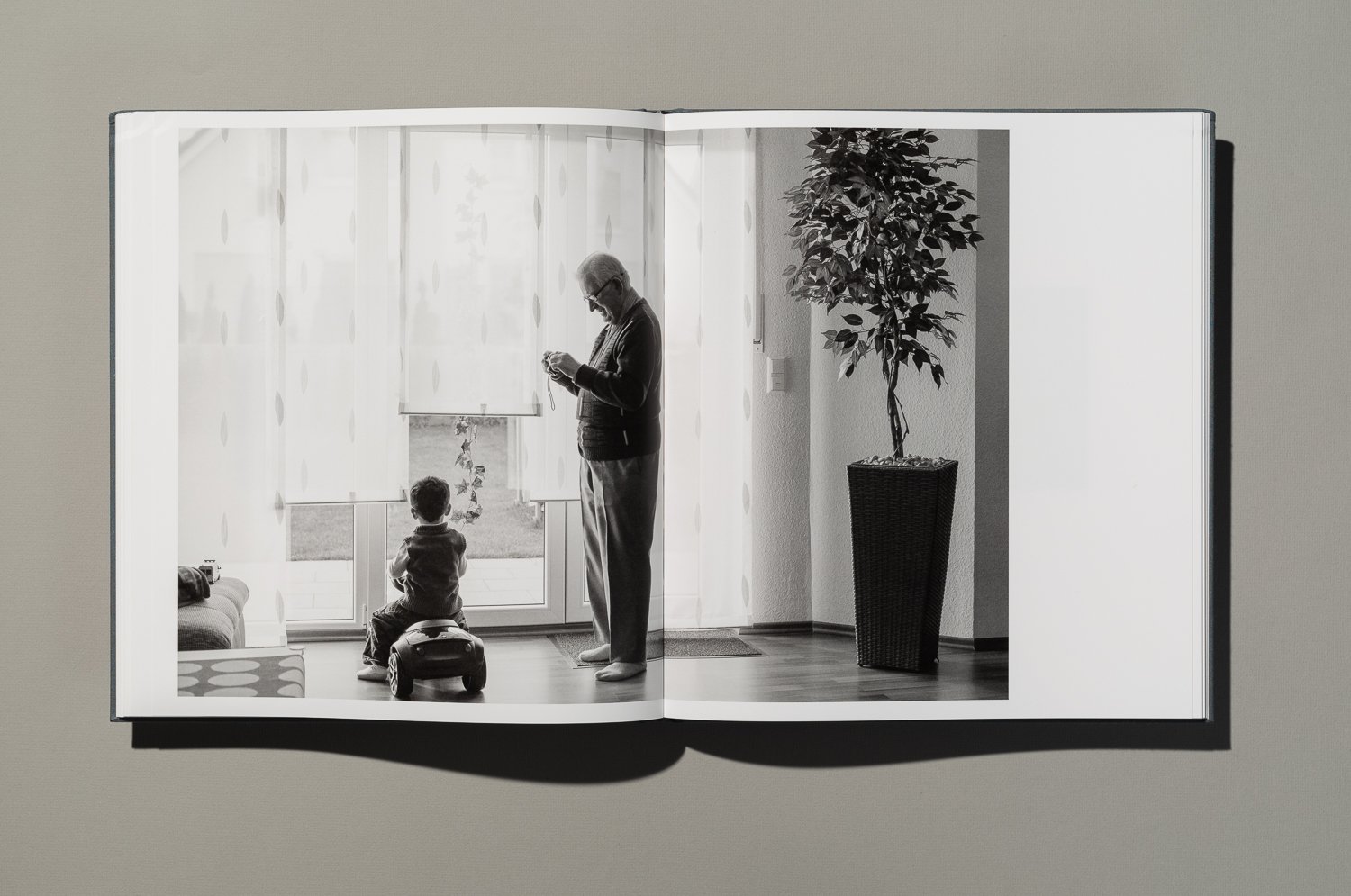

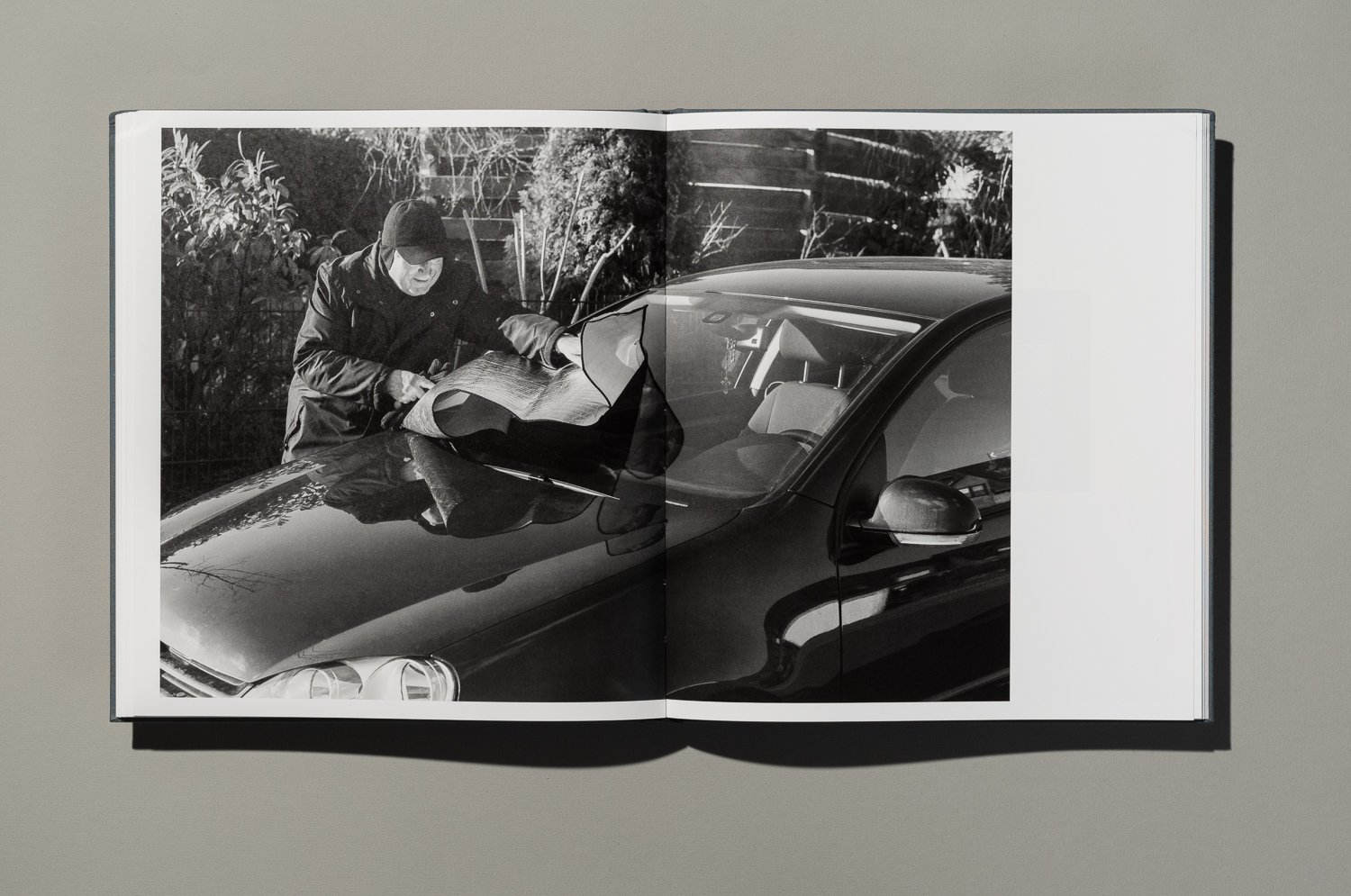

wind

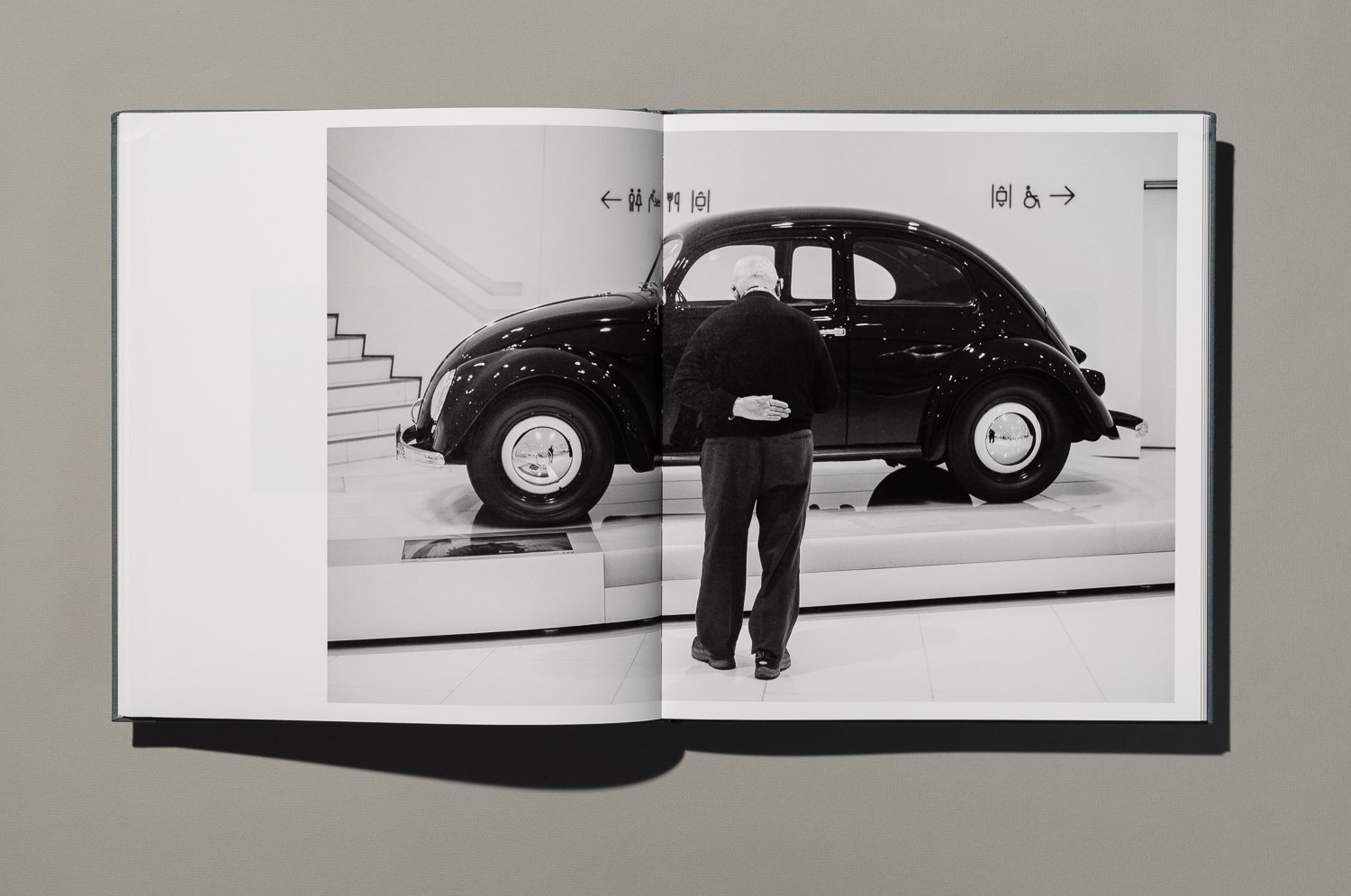

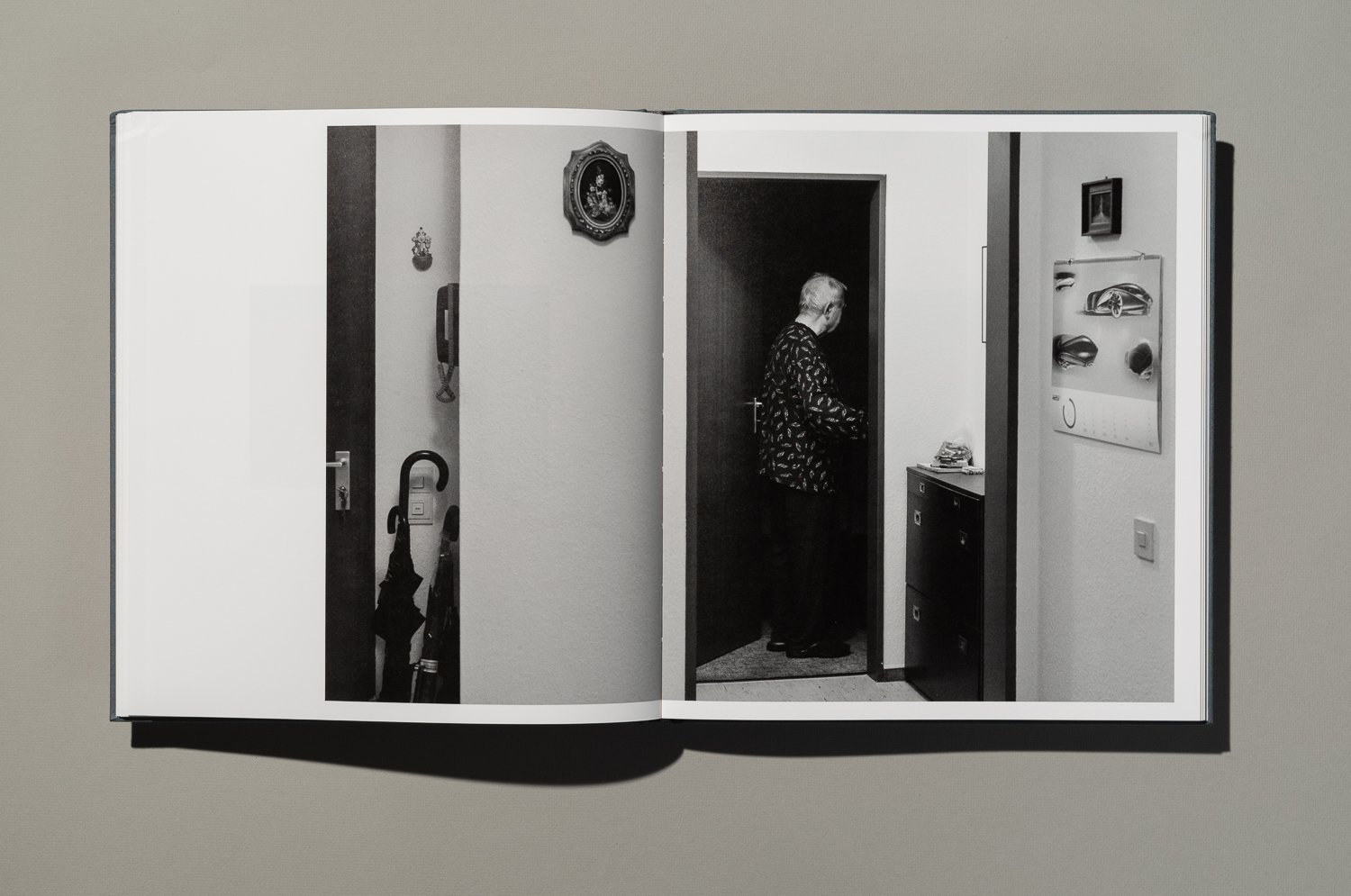

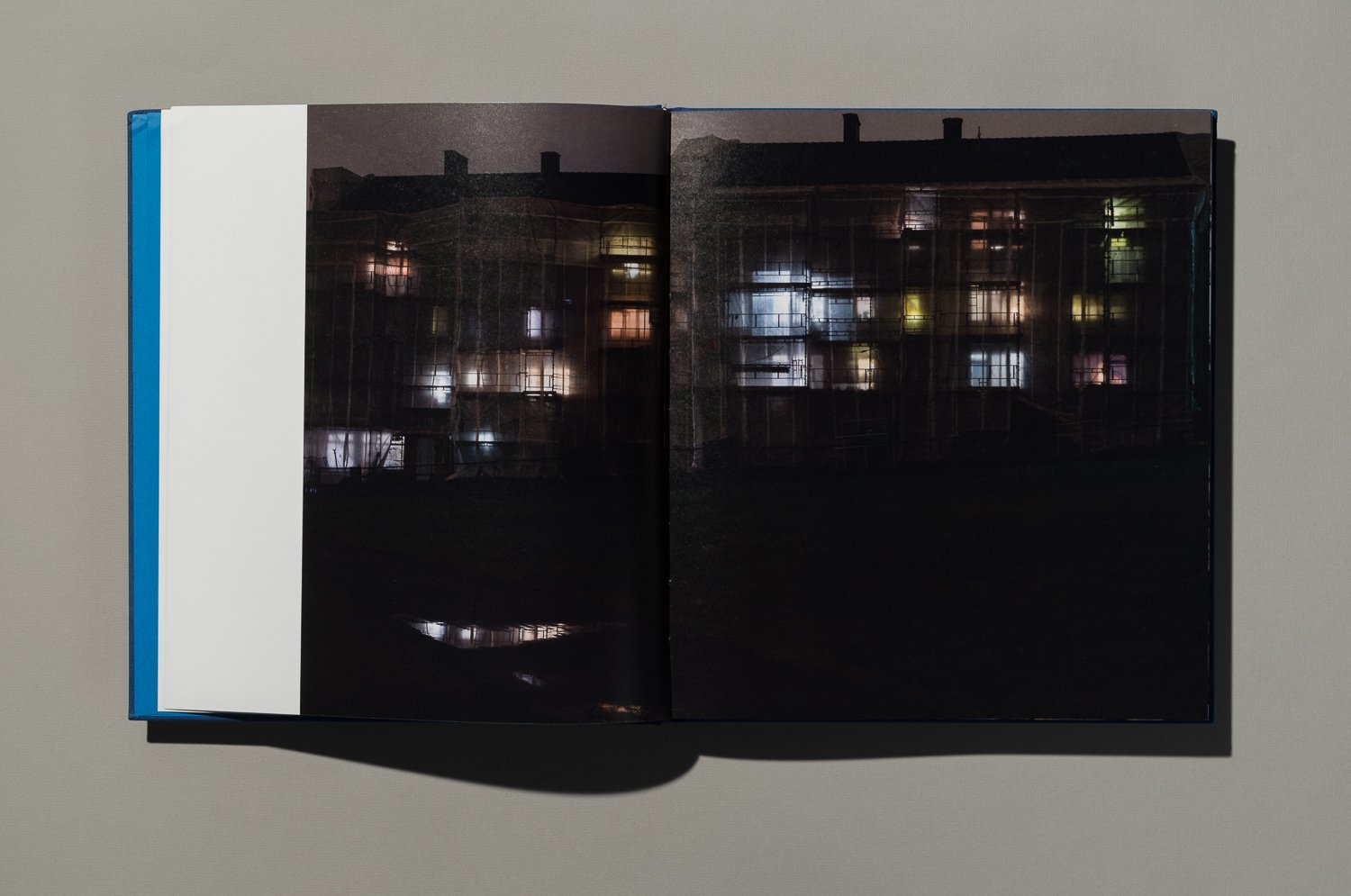

Every family speaks its own language. This allows us to talk without words and hear without sounds. As evidence of the relationship between father and son, Wind allows us to participate in the agency of the family that has formed the photographs. Their mechanisms are significantly influenced by the European past from which the family has evolved. The pictures invite us to interrogate what has happened through what we visually encounter. We are

obliged to do something with these pictures. We can agree or disagree with them.We can find them unfamiliar or find ourselves within them. If we accept this confrontation, resistances are created that allow us to acknowledge yesterday in today and shape tomorrow.

Excerpt from the essay by Sophie-Charlotte Opitz.

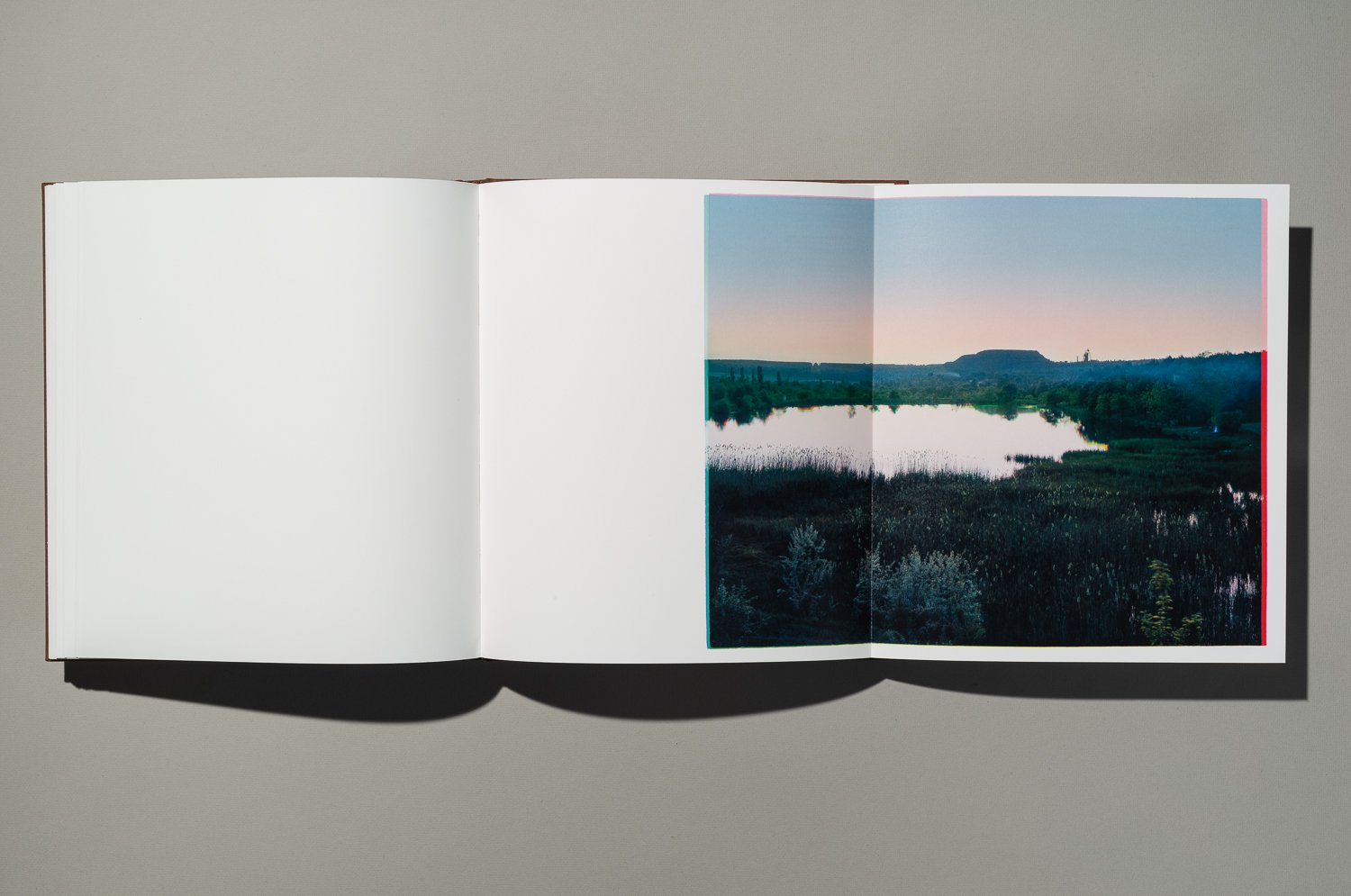

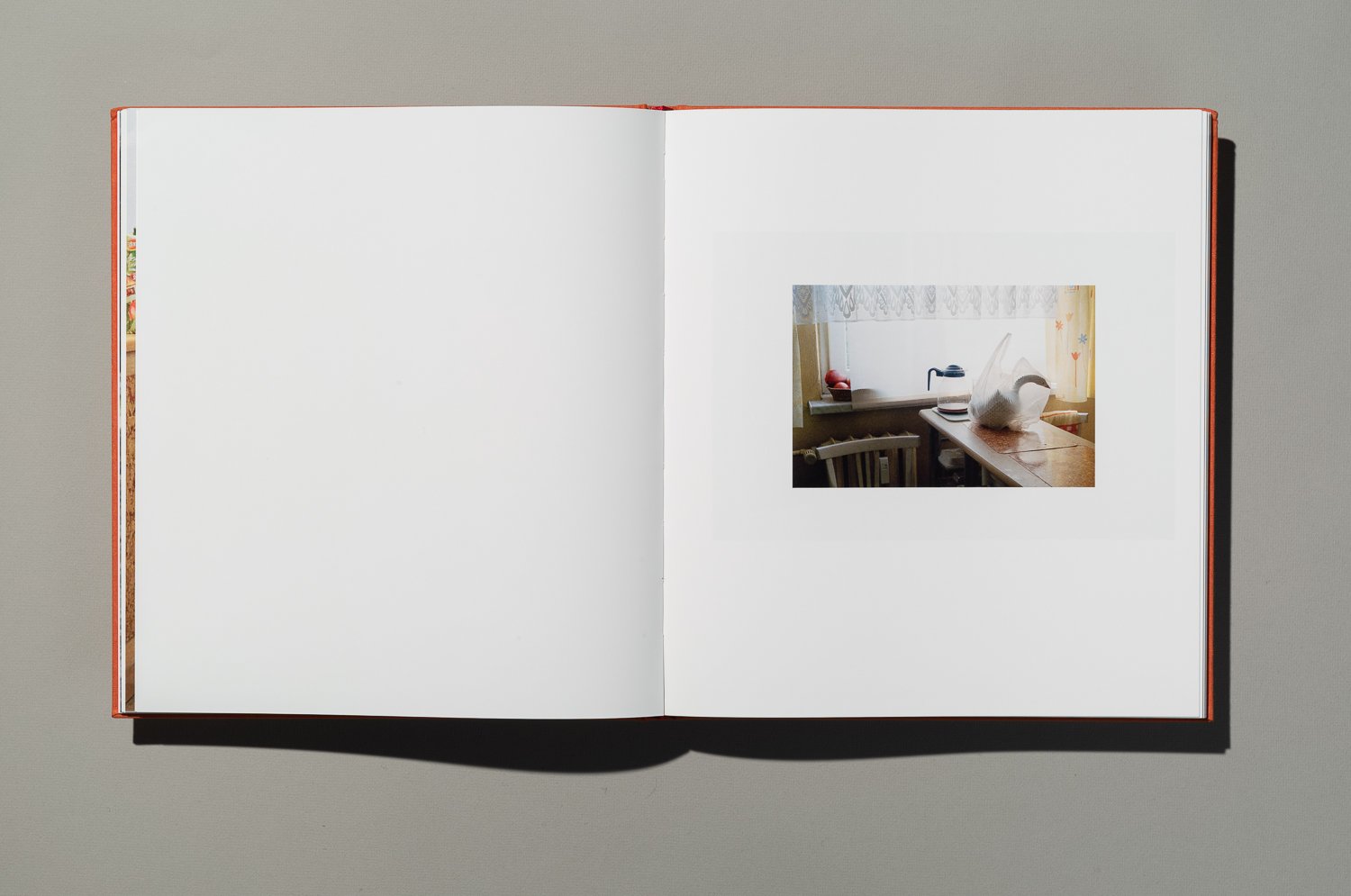

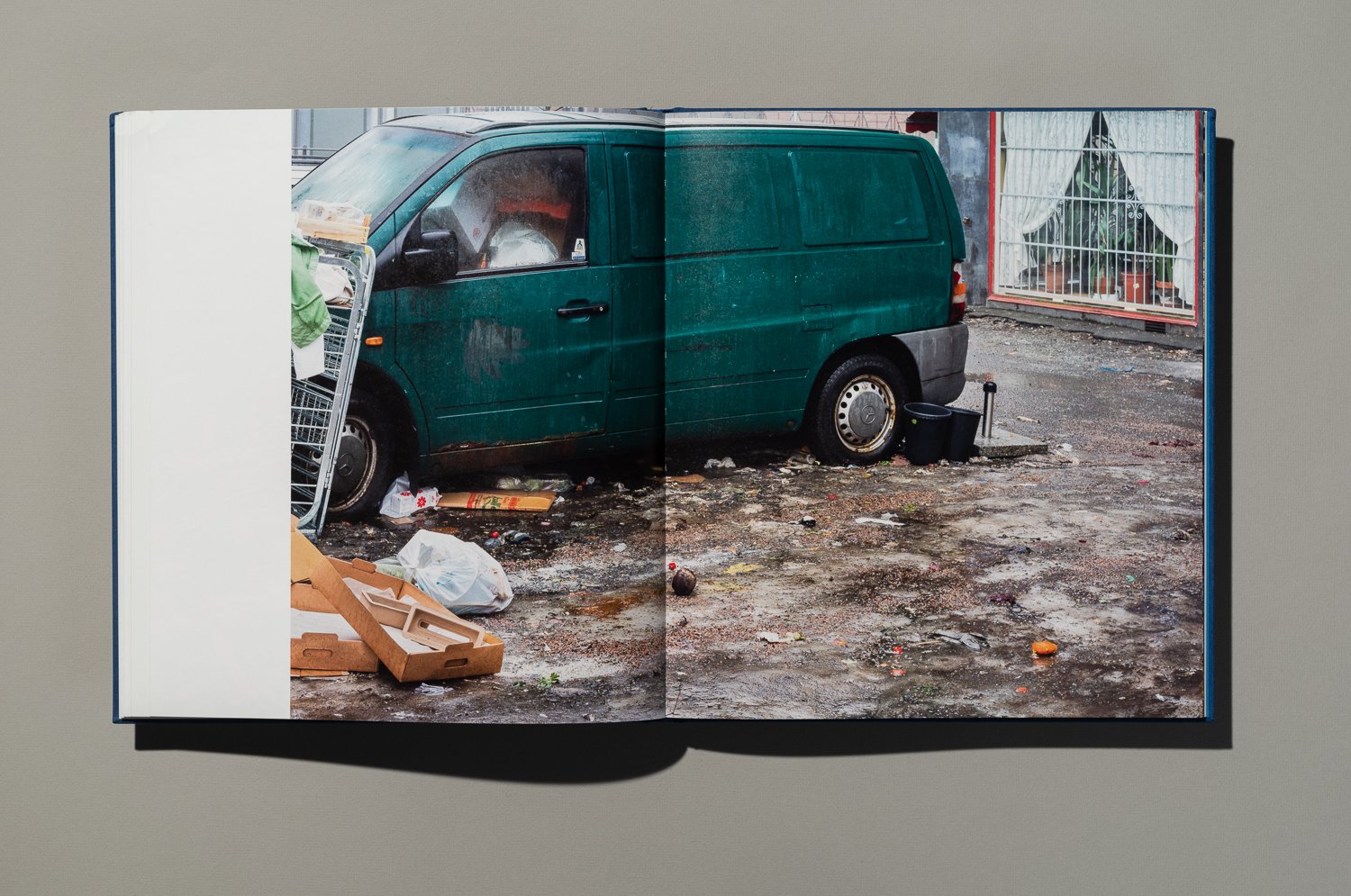

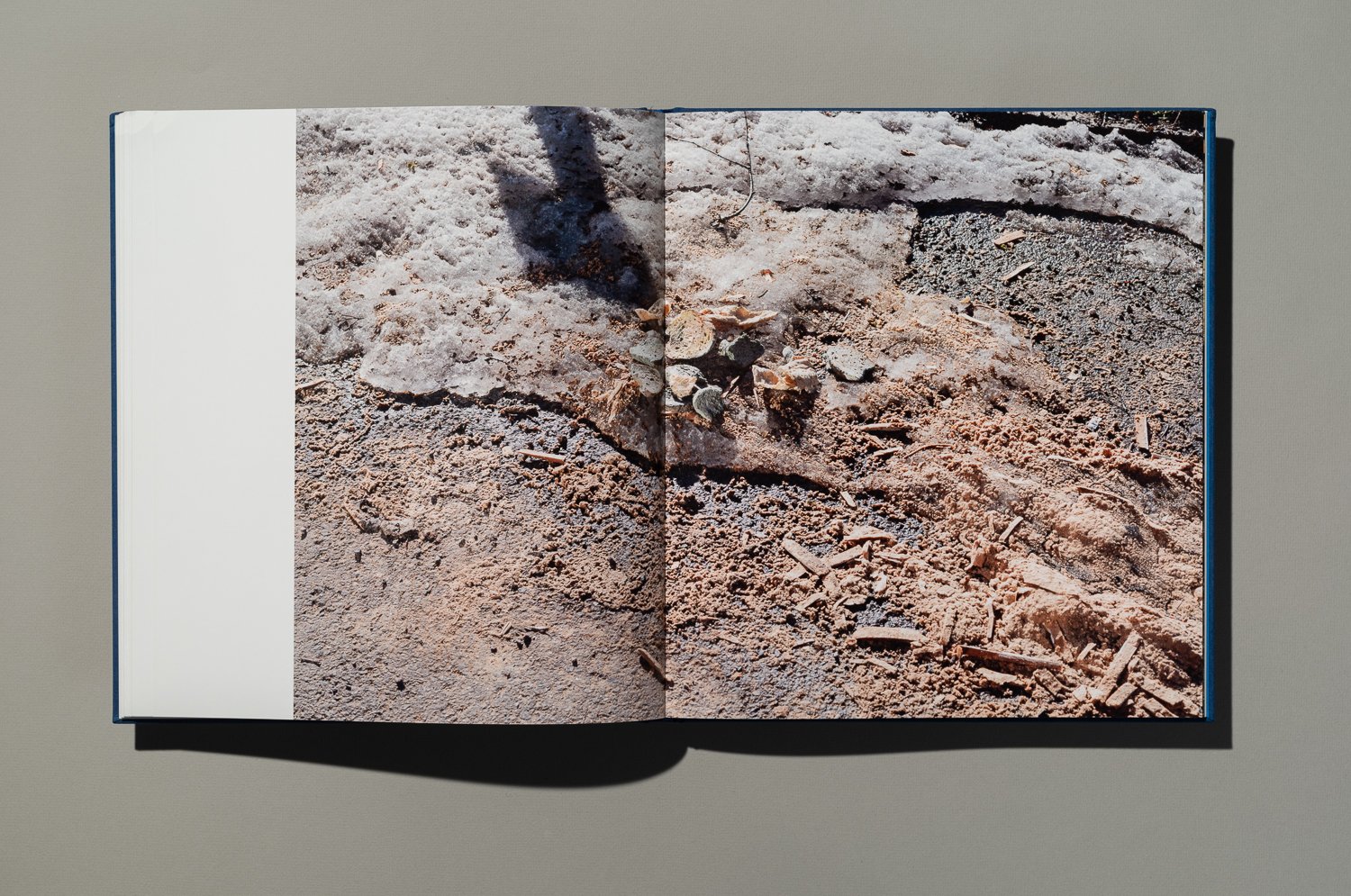

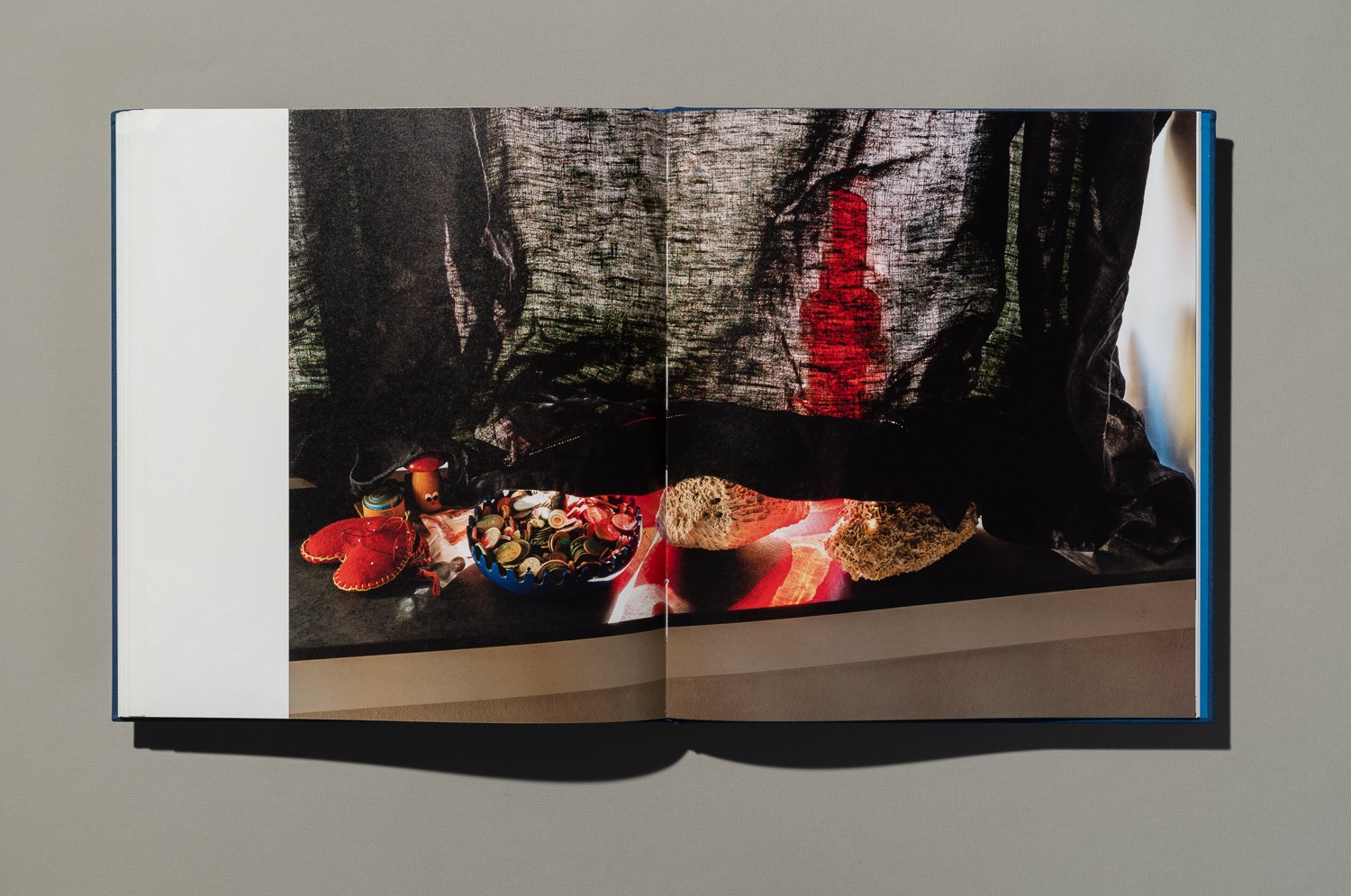

wasser

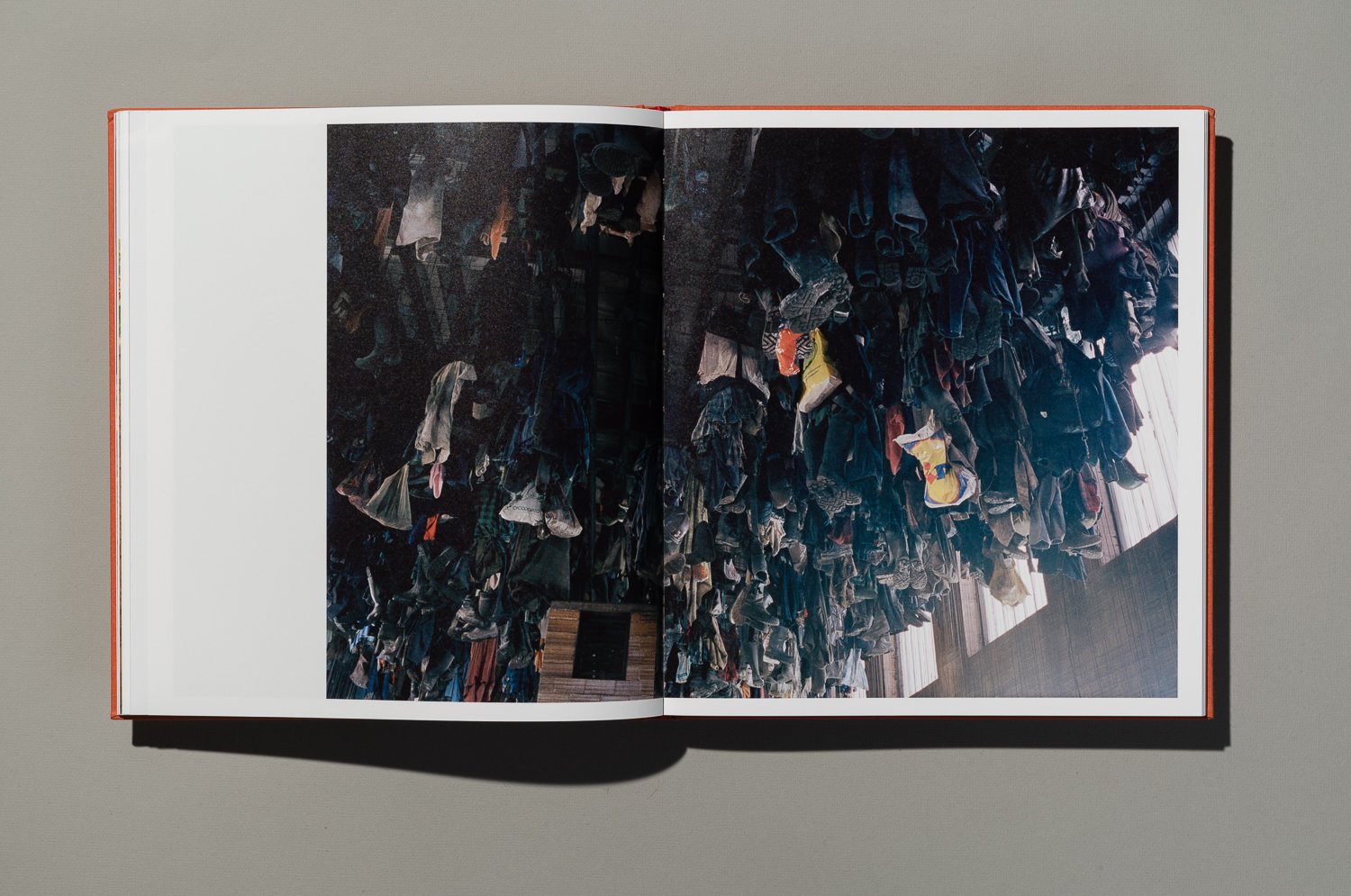

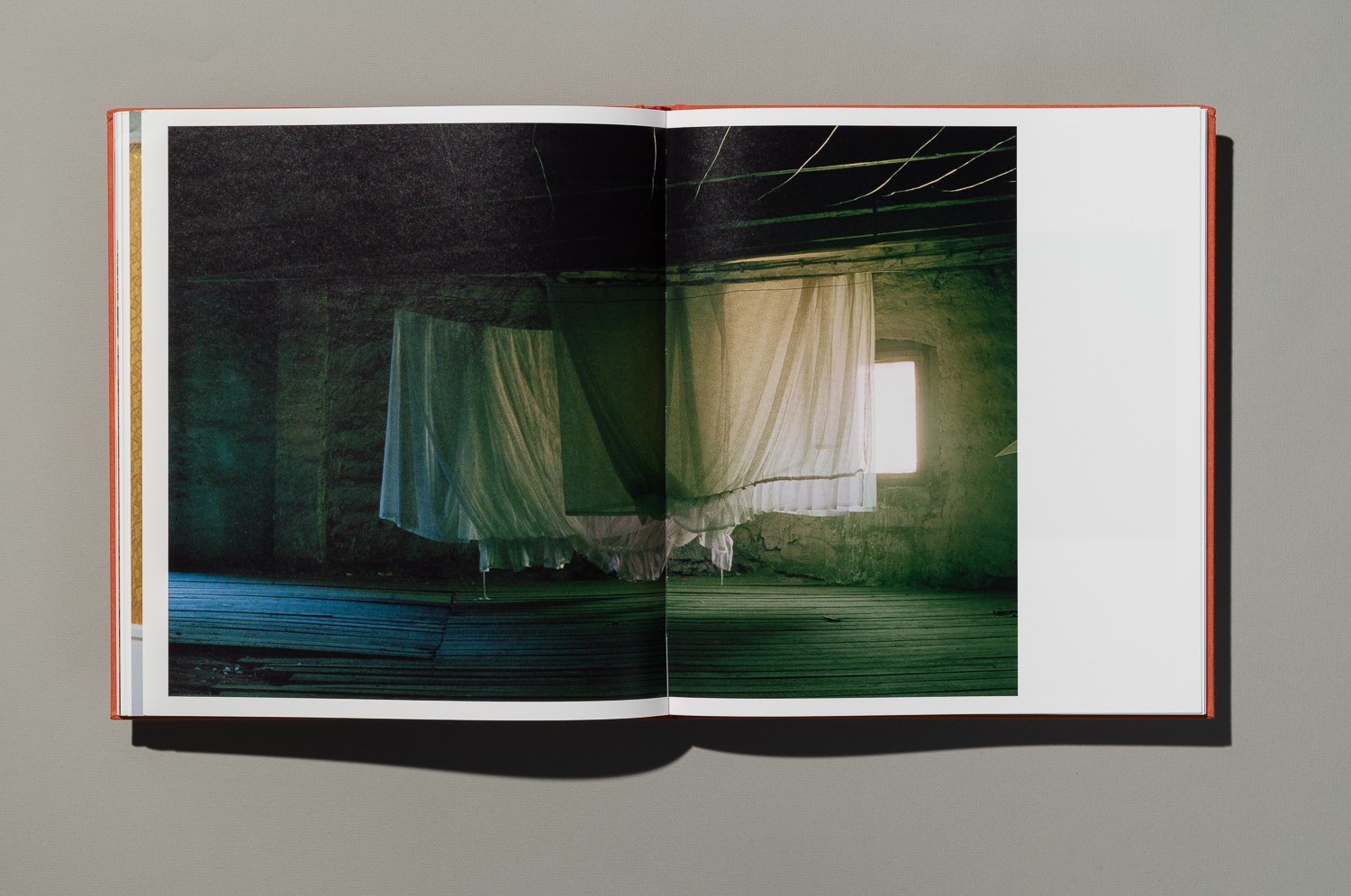

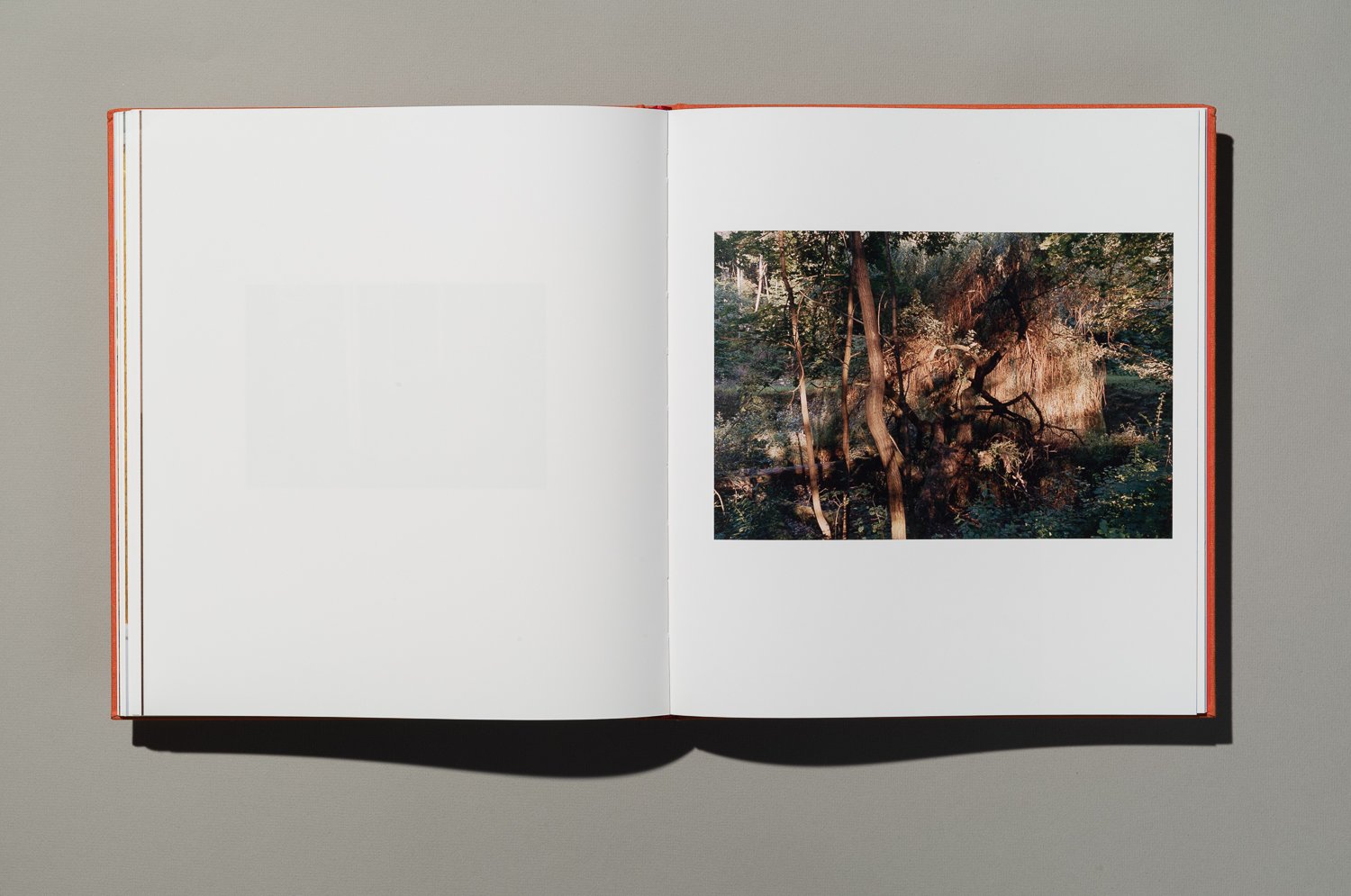

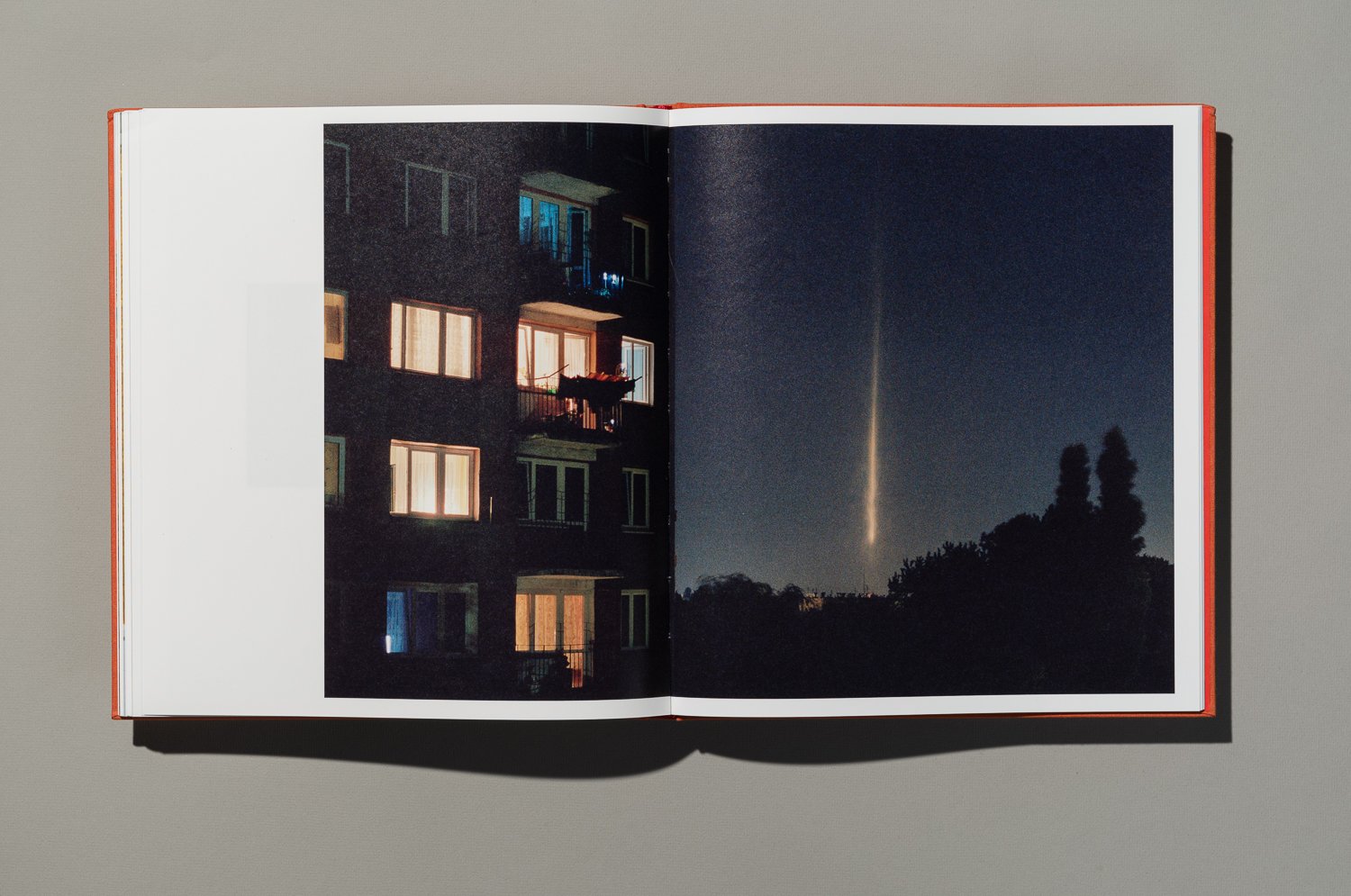

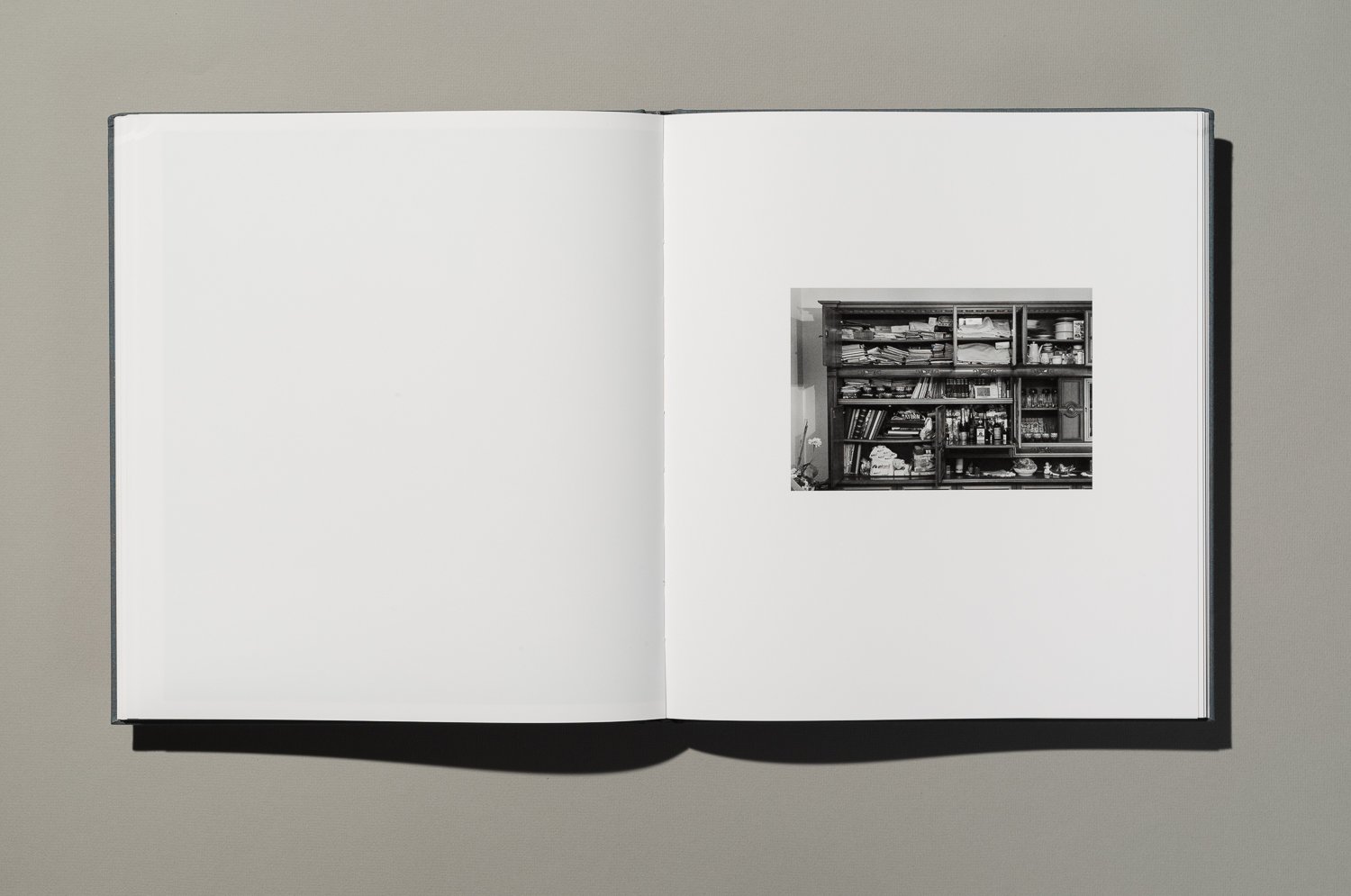

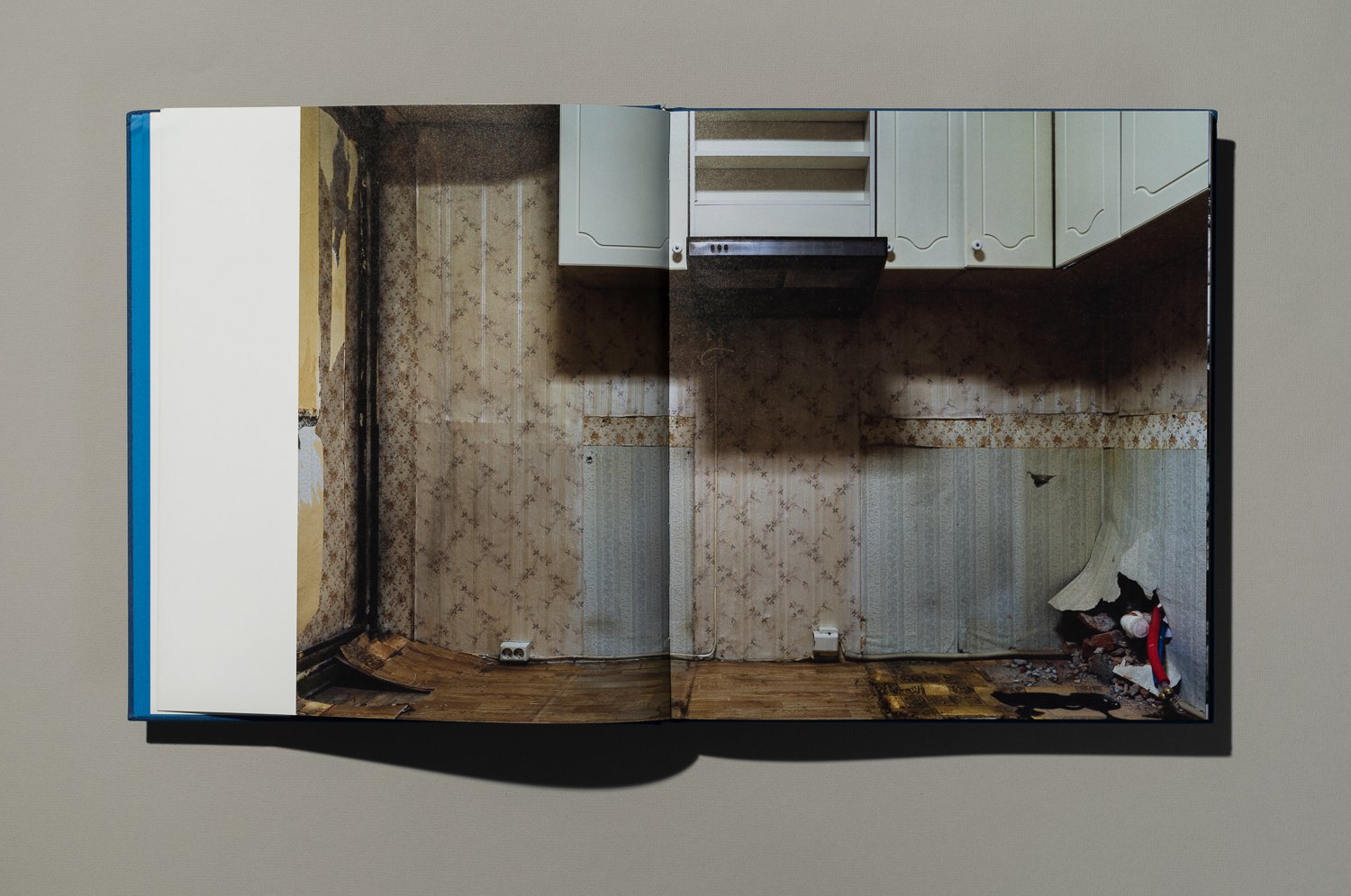

The island created, which seems to be both utopia and dystopia, is less a place of remembrance than a “springboard” to trigger movements that, in turn, initiate memories. For Damian, the journey into the past begins in the here and now, with himself. The apartment and its immediate surroundings transform from a concrete place to a practised space. His photographs are saturated with unstable visibilities that open up the space and, in their many voids, allow the viewer to interpret and decode, to remember and forget. Some photographs can pull you

under like bodies of water. They carry us into our innermost selves and internal spheres we can only enter through them. And while photographs sometimes appear violent, the scale of the affect depends on our identity and memories. What we see in these images, we create ourselves. It is in this silence that the viewer is left behind, looking at Wasser, wondering whether what we have just encountered is a photograph or, in fact, ourselves.

Excerpt from the essay by Sophie-Charlotte Opitz.